Employee/Industrial Relations

From Voice to Value: Positioning ERGs in the Employment Relations Climate

Overview

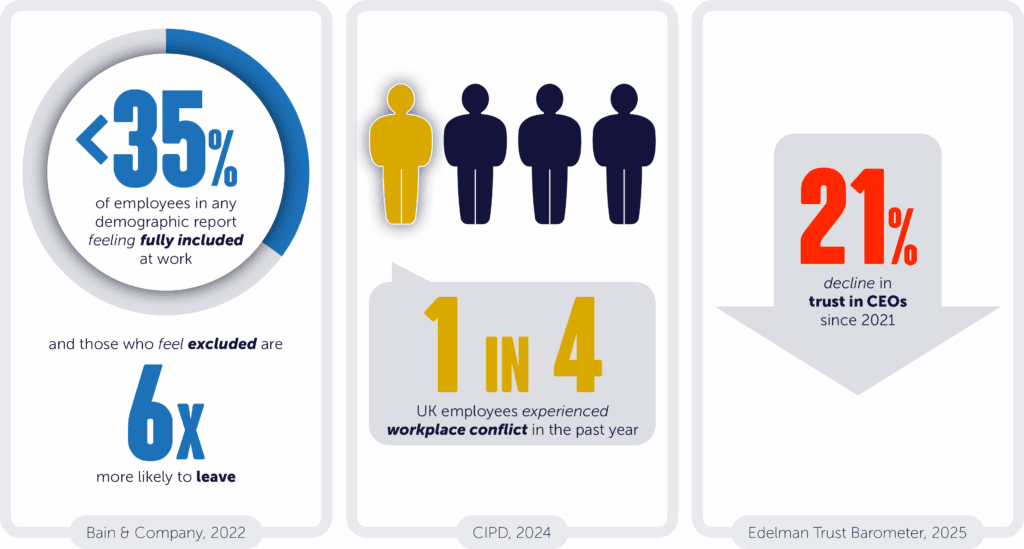

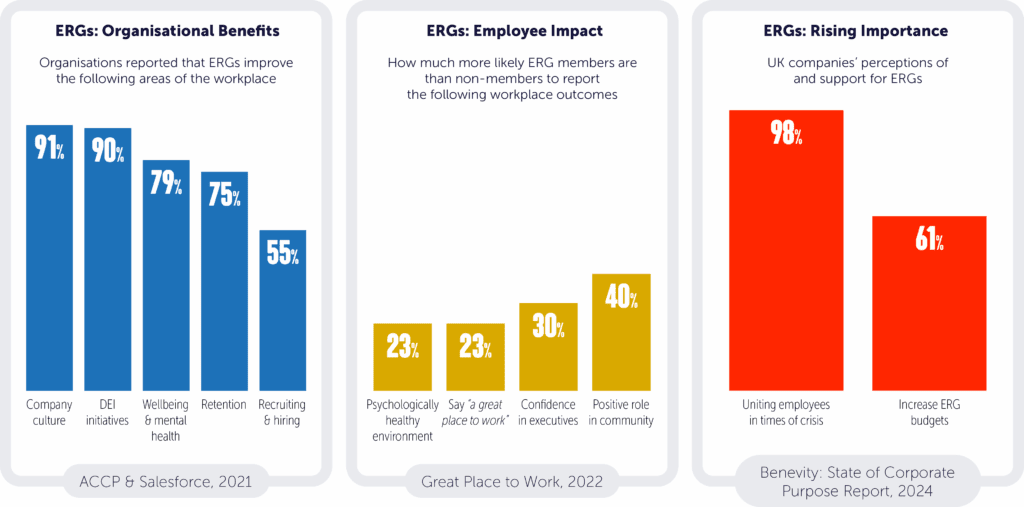

This article explores the role of Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) in today’s evolving employment relations climate. Now an established part of organisational life, the key question for HR leaders is less about whether ERGs should exist, and more about how they can be governed to maximise value and minimise risk. Drawing on research and case examples, the article sets out five principles of effective ERG governance. Each principle offers practical ways to align ERGs with existing consultation frameworks, helping them strengthen trust, culture and policy while remaining credible and sustainable within the broader employment relations landscape.

Introduction

Long-term shifts in how organisations engage with collective voice, combined with the growth of informal digital networks, continue to shape today’s employment relations climate. As Nick Dalton, former EVP HR at Unilever, explains:

“HR has been almost entirely individualistic. By neglecting the collective, organisations are only doing half the work they need to do. At the same time, employees are forming WhatsApp groups and digital networks that leaders cannot see, but which often shape opinion more than formal workplace channels.”

ERGs have grown as an important complement to traditional forms of employee voice. Originating at Xerox in 1970, they can be understood as organisational constructs that foster connection among employees who share similar social or identity-based experiences. Volunteer-led and employee-supported, ERGs are increasingly recognised as a valuable expression of authentic, non-union collective voice between employees and management.

As such, ERGs occupy a distinctive space within organisational life. Even without a codified role in employment relations, they can significantly influence perceptions of fairness, legitimacy and trust. This influence brings both opportunity and complexity. As Matthew Leger (2023) notes:

“With limited academic literature and empirical research on ERGs, we have a limited understanding of how to manage such groups to create the best chance for successfully adding value to work and business operations.”

With ERGs expanding in number and influence at a time of shifting employment relations, effective governance has never been more important. Clear alignment and supportive frameworks can help ERGs enhance collaboration, strengthen culture and trust and contribute meaningfully to policy and organisational cohesion.

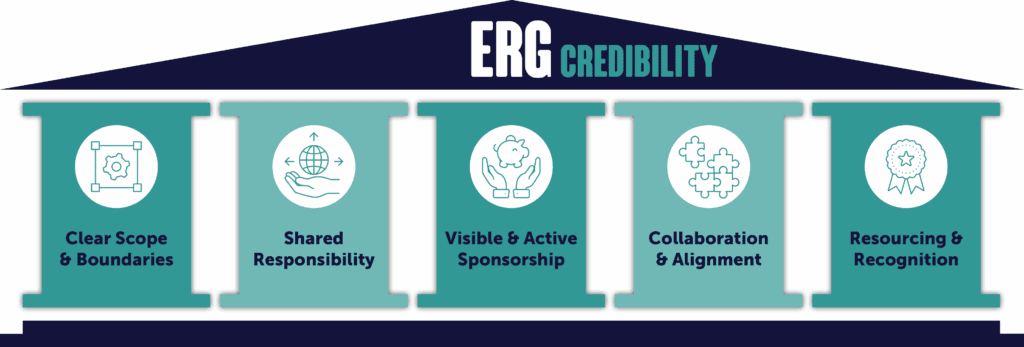

Principles for Governing ERGs in today’s Employment Relations Climate

The following five principles outline how HR leaders can position ERGs to contribute meaningfully to organisational trust, culture and policy.

1. Clear Scope and Boundaries

ERGs can be a strategic asset or a source of conflict. The difference lies in how clearly their role is defined. As Mustafa Faruqi, Employee Relations Strategy Director at BT, explains:

“I’ve seen some ERGs drift beyond their original scope and, in some organisations, start to take up individual cases and drive them as causes. It is important to bring them back to their intended remit while still valuing the important perspectives they bring.”

Without clear boundaries, ERGs risk drifting from community-building into quasi-representative roles that blur boundaries with existing consultation or union structures. This not only undermines established HR frameworks but can also push ERGs toward advocacy roles that create tension with management authority.

The task for leaders is to balance the valuable insight of ERG members’ lived experience with clear governance, so they remain empowered to influence culture and policy without straying beyond the organisation’s intent.

Examples from practice show that boundaries can be set without diminishing the value of ERG insight. In one organisation, gender and disability networks have been engaged to co-design policies on parental leave, carer’s leave and flexible working, helping to stress-test that changes were not only well-intentioned but workable. Their role was explicitly advisory, as one Former Large Headcount FTSE100 CHRO explained:

“We deliberately said to the ERGs, you are not responsible for changing the organisation. You are responsible for creating community and raising issues, but not for making these changes.”

Shell takes a similar approach during sensitive cultural moments. As Jamie Campbell, Employee & Industrial Relations Manager, put it:

“The organisation takes the overall accountability on what the company response and position will be, but we develop that decision and how we communicate it in partnership with the ERGs.”

For example, during the 2025 Supreme Court ruling in Scotland on the definition of sex, Shell engaged ERGs as key stakeholders. This allowed leaders to anticipate employee concerns and work alongside networks, while the company retained final authority.

Clear role definition is therefore a critical governance safeguard. It ensures ERGs enrich policy and crisis management while keeping accountability with leadership.

The principle is straightforward: ERGs advise, leaders decide.

2. Broadening ERGs for Shared Responsibility

A recurring concern for HR leaders is how ERGs affect the overall voice system. While identity-based groups play a vital role in supporting underrepresented employees, if they operate too narrowly they risk becoming disconnected from the wider workforce. This can create perceptions of exclusivity or foster a sense that ERGs speak only for a subset rather than the whole organisation.

Some organisations are addressing this by broadening remits to focus on shared workplace issues and embedding networks more firmly into the employment relations climate.

At Shell, for example, Jamie Campbell describes how their UK women’s network rebranded as Balance to “actively involve other genders in equity discussions and activate stronger allyship,” recognising equity as an organisational issue rather than one tied to a single demographic.

Severn Trent has followed a similar path. As Sunil Purba, Employee Relations Manager, explains, ERGs were recently rebranded from ‘Advisory Groups to ‘Colleague Networks,’ with communities such as Women in STEM widening their remit to represent women more broadly across the business.

Broader remits help ERGs integrate into organisational culture, reduce the risk of factionalism and frame inclusion as a shared responsibility. For HR leaders, this shift matters because it aligns ERGs with the principles of constructive employee relations: finding common ground, building shared agendas and reinforcing rather than fragmenting organisational cohesion.

3. Visible and Active Sponsorship

Executive sponsorship is not symbolic but structural. Sponsors give ERGs credibility across the workforce whilst keeping them connected to organisational authority and governance frameworks. Without this connection, ERGs risk being seen as peripheral or lacking the alignment needed to influence organisational priorities effectively.

Research by Theresa Welbourne shows that executive sponsorship is now a mainstream governance mechanism, with the most effective sponsorship coming from the highest levels of leadership. In her survey, 96% of organisations had executive sponsors for their ERGs, most commonly from the C-suite (73%) followed by senior VPs (48%).

Executive sponsorship has what talent services firm Seramount describes as a “ripple effect” throughout the organisation, with employees taking cues from their leaders. However, to be effective, the role of the executive sponsor must extend past visibility. As explained by Alexandra Mesteru, Global HR Policy Lead at Shell:

“Sponsorship shouldn’t be limited to creating visibility or approving budgets. True sponsorship means engaging with the ERG as a strategic partner – helping them shape their goals and focus their efforts where they can have the greatest impact.”

In practice, sponsors play several roles: formalising the relationship of the ERG to the organisation, establishing a direct line of communication with business leadership and providing the governance that makes ERGs credible. They also act as guardrails, ensuring ERGs remain collaborative and aligned with organisational purpose.

Organisations take different approaches to ensure executive sponsors commit fully to their role. At Aviva, for example, every executive committee member sponsors an employee community in pairs and attends quarterly meetings. Pairing sponsors creates visibility between peers, which builds accountability and gentle pressure to stay engaged.

Ultimately, executive sponsorship gives ERGs the authority, alignment and visibility they need to be credible partners in the employment relations climate.

4. Encouraging Collaboration Across ERGs

“In any large organisation with diverse communities and a broader majority, there is always noise about who gets the airtime, who gets the space and who gets heard.”

Athalie Williams, former Chief Human Resources Officer, BT

Uncoordinated ERGs can unintentionally fragment employee voice and create tension between groups with different perspectives on shared issues. As explained by Mustafa Faruqi, Employee Relations Strategy Director at BT:

“People from one network can feel pitched against people from other networks when they have competing perspectives on a shared issue.”

Such tensions often arise around workplace facilities, policies, or resources, where compromise can be difficult.

By contrast, collaboration channels ERGs into shared forums that strengthen both the network ecosystem and the wider employee relations climate. Many workplace challenges span multiple communities, and cross-ERG collaboration can generate innovation, new perspectives and broader legitimacy. Theresa Welbourne likens this to “collision theory,” where new outcomes emerge when groups connect and ideas intersect.

Organisations can encourage this through structures such as diversity and inclusion councils, where ERG chairs collaborate, align priorities and collectively feed insights into HR.

“We often see networks supported by a diversity and inclusion council, where the chairs of each group sit together. They feed collectively into HR and also stay connected on what each group is doing.”

Rosie Clarke, Principal Consultant, Inclusive Employers

Collaborative structures like these prevent ERGs from working in isolation and offer a two-fold benefit: for ERGs, stronger ecosystems and greater visibility; for organisations, a more unified and constructive employee voice that supports innovation and credibility in decision-making.

5. Resource and Recognition

Providing ERGs with time, budget and recognition makes them sustainable and credible parts of the employment relations landscape. With meaningful support, ERGs can strengthen employee voice, develop future leaders and contribute directly to organisational goals.

Organisations sustain ERGs in different ways. One approach is formal time allocation. Rosie Clarke, Principal Consultant at Inclusive Employers, notes that ERG participation, particularly at leadership level, is often “carved out of their day job.” In practice, this can mean taking on fewer projects or clients so that ERG responsibilities are formally recognised.

Another method is direct financial support. Providing ERGs with budgets and annual objectives signals legitimacy and alignment. As John Whelan, Director at Corporate Research Forum, explains:

“Many organisations give them budgets and give them annual objectives. They really treat it as if it is a job in a business.”

Some organisations are going further by evolving ERGs into what Theresa Welbourne describes as Strategic Resource Groups (SRGs). This reflects a shift from identity support alone toward integrating ERG activity with business strategy, leveraging employee insight for innovation and growth.

For example, American department store Macy’s partnered with its Hispanic ERG to design a culturally relevant Quinceañera (a traditional 15th birthday celebration for girls in Hispanic communities) e-gift card. The initiative generated more than $250,000 in its first year, scaled nationally and repositioned the ERG as a strategic business partner.

This strategic approach also extends to talent development. At Severn Trent, ERGs are viewed as part of succession planning and capability-building. As Sunil Purba, Employee Relations Manager, explains:

“How we look at our networks is more strategic. We are thinking about succession planning and the skills we will lose through retirements, and using ERGs alongside our talent groups to plug those gaps while advancing our wider goals”.

Similarly, at Mitie, ERGs are recognised as talent pipelines to increase representation at senior levels, with several ERG chairs progressing into high-potential programmes.

In essence, support sustains ERGs and recognition makes them credible, transforming them from voluntary networks into valued partners in organisational strategy.

Conclusion

ERGs are now an established feature of employment relations. They create value by fostering connection and providing authentic channels for employee voice, offering qualitative insights that formal mechanisms can overlook. To realise their full potential, HR leaders need to ensure clear boundaries, support and alignment so ERGs strengthen culture and policy while operating within credible governance frameworks. In doing so, HR leaders can ensure ERGs remain a source of connection, insight and trust within a fast-changing employment relations landscape.

Key Takeaways

- ERGs are a growing channel of voice providing influence and connection across the workforce.

- Clear scope defines their role in community and consultation rather than casework or bargaining.

- Broader remits reduce silos by encouraging shared responsibility across the workforce.

- Executive sponsorship anchors credibility through visibility and alignment with leadership.

- Collaboration turns competing voices into a unified channel that brings innovation, legitimacy and stronger impact.

- Resourcing sustains ERGs by giving them the time, budget and recognition needed to endure.

References

Amire, R. and Lee, D. (2024) The Great Transformation: How ERGs and Inclusive Leadership Drive Workplace Innovation. Great Place To Work

Association of Corporate Citizenship Professionals (2021) An Analysis of Employee Resource Groups: Summer/Fall 2021 Survey. ACCP

Bain & Company (2022) The Fabric of Belonging: How to Weave an Inclusive Culture

Benevity Impact Labs (2024) The State of Corporate Purpose 2024. Benevity

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) (2024) Good Work Index: Survey Reports

Edelman (2025) 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer: Trust and the Crisis of Grievance

Erb, M. (2024) ‘Leaders are Missing the Promise and Problems of Employee Resource Groups’. Great Place To Work

Jennifer Brown Consulting and Cisco (2010) Employee Resource Groups that Drive Business, pp. 17-18

Leger, M. (2023) Building High-trust Workplaces: The Role of Employee Resource Groups in Fostering Stronger Employee-Employer Relationships. American Enterprise Institute

Pillans, G. and Wallace, W. (2025) Creating an Inclusive Culture: Report. Corporate Research Forum, pp. 30-31

Scully, M. (2009) ‘A Rainbow Coalition or Separate Wavelengths? Negotiations Among Employee Network Groups’, Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 2(1), pp. 74-91

Seramount (2024) The 2025 ERG Survival Guide, p. 15. Seramount / EAB

Welbourne, T.M. (2024) ERGs at the Crossroads: The State of Employee Resource Groups Report – 2024. University of Southern California, Marshall School of Business, Center for Effective Organizations, p. 24

Research Participant List

Jamie Campbell, Employee and Industrial Relations Manager, Shell

Rosie Clarke, Principal Consultant, Inclusive Employers

Nick Dalton, former EVP HR, Unilever

Mustafa Faruqi, Employee Relations Strategy Director, BT

Alexandra Mesteru, Global HR Policy Lead, Shell

Sunil Purba, Employee Relations Manager, Severn Trent

Athalie Williams, former CHRO, BT

John Whelan, Director, Corporate Research Forum

MEMBER LOGIN TO ACCESS ALL CRF CONTENT