Talent, Leadership and Learning

Speed Read: Strategic Workforce Planning – Unlocking Future Capabilities to Drive Business Success

SPONSORED BY:

The ability to develop, implement and adapt new business strategies in a fast-paced, agile way has become essential to business survival. In practice, business strategies often fail, not because they are wrong, but because they are not implemented effectively. People strategy can be an especially weak link, as companies pay insufficient attention to the people actions required to execute the strategy, or are too slow to respond. This is where Strategic Workforce Planning can form a bridge between business and people strategy.

What is Strategic Workforce Planning and why does it matter?

Strategic Workforce Planning (SWP) is an essential discipline that can help companies evaluate the feasibility of different strategic options. Its goal is to work out what’s needed in terms of people and organisation to implement the business strategy, where the gaps lie between current supply and future demand, and to build action plans to develop the workforce to support long-term business goals. It’s a risk management tool enabling organisations to identify and manage the people and organisational risks associated with a chosen course of action.

SWP is key to avoiding a trap that many organisations fall into when developing people strategies: they simply extrapolate forward from today and fail to take account of how their business context will change and what that means for the workforce.

We find that organisations are increasingly recognising the value of SWP and are looking to improve their practice. However, strategy development generally, and SWP specifically, tend to be underdeveloped skills for the HR function and many organisations have struggled with implementing SWP. We have heard many stories of false starts and failed attempts.

Positioned correctly, and with appropriate business sponsorship and support, SWP gives HR the opportunity to have a voice in strategy discussions and improve the quality of discussions by focusing on the talent required to execute strategy and the feasibility of the options being considered.

We are likely to see significant strategic repositioning of businesses as we emerge from the pandemic. This will drive demand for SWP and the need for HR to demonstrate expertise in this area.

The purpose of this speed read is to define what SWP is (and isn’t), to explore how to develop a practical and effective approach to SWP, and how to overcome the typical barriers faced by HR functions. We also consider how approaches to SWP can be made more agile, adaptive and responsive to change.

In this section generally it is not always clear whether you are talking about business strategy, people strategy or both. Point not quite made that the people bit often a weak point in business ambitions. Also that people affect business plans not just linear the other way round.

Definition: Strategic Workforce Planning

SWP is a process that’s designed to align a company’s people and organisation with its business direction. It involves examining future workforce needs as determined by the business strategy, analysing the current organisation, identifying gaps between the present and future, uncovering risks to strategy execution, and taking action so the organisation can accomplish its mission and goals.

From our research we would make the following observations:

- The purpose of SWP is to improve the quality of conversation about what it will take to deliver the future vision of the business, in terms of talent, people and organisation. It seeks to uncover assumptions, explore options and surface risks.

- Effective SWP contributes to productivity and overall business performance by looking not only at the size, shape and capability of the workforce required to deliver the business strategy, but also at the total cost (including direct employees and others).

- Run effectively, SWP takes a ‘future-back’ view, identifying the steps that need to be taken to progress to the future state envisaged by the strategy.

- SWP looks at the macro level to identify pinch points that determine the feasibility of different strategic options, or even put new ones on the table. It should not just be an exercise that happens once strategy has been determined. Positioned correctly, it can help improve the quality of strategic decisions as they are identified and refined.

- It also supports effective organisation and work design. Sometimes the actions required involve changes to jobs, not people.

- SWP highlights where action is needed now for the organisation to be in a position to address issues coming down the line.

- SWP is as much a mindset as a formal process. It’s about creating the conditions for managers to think deeply and systematically about the workforce that’s required to execute strategy effectively. It creates the habit of challenging assumptions and looking for evidence to inform employment decisions.

- SWP is not an exact science. It is unlikely to provide answers that are 100% correct and requires leaders to exercise judgment and deal with ambiguity. It gives broad brush outcomes rather than detailed forecasts. It needs to be combined with scenario planning to explore uncertainty and map out alternative futures.

- The pandemic has shown that SWP can happen on a relatively short timescale. Some organisations have found that using a stripped-down version of the methodology we set out in this speed read enabled better short-term decisions.

- It’s essential that SWP is integrated into the business planning process, not run as a standalone process by HR.

SWP seeks to address questions such as:

- What strategic capabilities will the business need to master to execute its strategy?

- What new capabilities will we need to build or acquire? What capabilities do we currently have that we need to maintain or develop? Which capabilities that we have today will no longer be required – and how should we tackle the surplus?

- Where will our changing needs require reorganisation or changes to content of our work and jobs?

- How might we build the capabilities we need to develop? Should we buy, build or borrow? Where will automation replace or change our people needs?

- What talent requirements emerge from our strategic plan? Which are our most important talent segments? What talent interventions should we initiate in terms of recruitment, development and deployment?

- Which kinds of job roles and kinds of people are critical to delivery of the strategy and likely to be difficult to get hold of? How do we define and shape them?

- How do we match talent to add value in those roles, by matching our best people to our most critical roles?

- How can we best prepare the current workforce for the future?

- What big bets or bold moves do we need to make to acquire the future capability we need?

- What are the risks if we fail to take action to develop our workforce and how can we mitigate them?

- Where is future workforce a serious enough constraint to make us re-think aspects of our business strategy?

CRF Strategic Workforce Planning Model

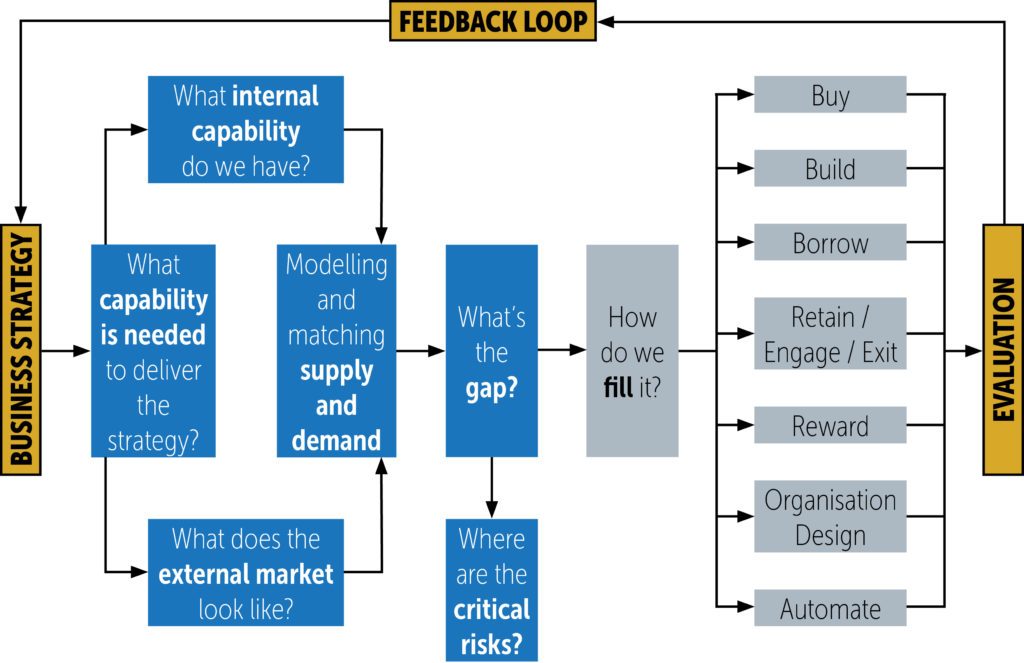

CRF’s framework for Strategic Workforce Planning is set out as a series of questions. They explore the future workforce needs emerging from the business strategy, current supply, actions required to close the gap, and include a feedback loop to evaluate actions taken and inform future iterations of the process.

The following principles underpin the model:

- Start with the business strategy. The purpose of SWP is to identify workforce actions required to accomplish the business strategy. This means starting with an understanding of the business, which involves looking at both the external context and the internal situation. The context of the organisation – its political, social, economic and technological environment, the nature of competition and the pace of change – will drive choices around what to do, when and where.

- Take a ‘future-back’ perspective. It’s important to start by articulating the organisation’s ‘North Star’. That is to describe a clear and compelling vision of where the organisation is heading, and what good will look like when it reaches that destination. SWP then works back from that point to set out the work that needs to be done to meet those objectives and the interim goals along the way.

- Think of SWP as a system. Thinking systemically involves connecting what happens within the organisation with its external environment. It also involves identifying the consequences of one set of actions within other parts of the organisation system. For example, a digital transformation strategy might require making the company more attractive to scarce talent such as data scientists or cyber security experts. This would require action across various elements of the employment value proposition, including physical location of work, reward, organisation culture, performance management etc.

- Positioning SWP in the wider employment strategy. While the focus of SWP is principally resourcing, development and work design, it both shapes and is informed by the wider employment strategy. The employment strategy addresses questions such as: “What sort of employer are we aiming to be?”, and “What are the culture, values and principles for managing people that underpin our employment proposition?”

- SWP is an iterative process. Although SWP may be drawn as a linear sequence of steps, in practice it is an iterative process. Later stages of the process may require earlier assumptions to be revisited. Plans need to be re-evaluated on an ongoing basis.

- A partnership between HR and business stakeholders. While HR may be responsible for designing the SWP process and delivering the plan, it is essential to engage key stakeholders from the outset in owning the process and its outcomes. Success will depend on business leaders, in particular finance and strategy functions, buying in to the need for SWP and committing time and resources to do the work.

The CRF model is set out as series of questions that need to be answered in developing the workforce plan. Let’s consider each of the questions in turn.

1. WHAT CAPABILITIES ARE NEEDED TO DELIVER THE STRATEGY?

Before getting into detailed planning around roles and positions, it’s important to identify the critical organisational capabilities required to build or sustain competitive advantage. Note that building organisational capabilities may require actions that are linked to talent, but will almost always include other factors. Organisational capabilities are bigger than (but include) talent.

Take ‘consumer insight’, a capability that many organisations cite as the key to unlocking competitive advantage. In practice, developing this capability is likely to require a combination of:

- Building technology assets that enable the collection and aggregation of data from multiple sources – to understand your customers, how they behave and what they think of you

- Building data analytics capacity (roles) and skills – to turn that data it into actionable insights

- Building innovation processes that are agile and human centred – to respond fast and build products that consumers want

- Assigning accountabilities and decision rights to ensure that when you bring it all together, you strike the right balance between analytical rigour and creativity to make choices that work commercially

- Nurturing a behaviour of curiosity and insightfulness everywhere.

Addressing this range of needs implies a combination of actions that develop the workforce and the supporting organisational infrastructure. While teasing out the critical capabilities is an essential stepping stone in getting from business strategy to workforce actions, in practice leaders often find it difficult to break the business strategy down into tangible capabilities and bring those to life in terms of the day-to-day work of the organisation.

Leaders will often simply extrapolate forward from today when in fact a change in strategy demands the development of new capabilities or a shift away from the organisation’s current core strengths. Understanding how the work of the organisation will change is the essential bridge between strategy and identifying future capabilities.

This stage must therefore answer questions such as:

- Is there new work that we will need to do to be successful in the future? (developing new brands, products or services, or operating across different sales channels etc.)

- Or work that will be done in a different way? (faster innovation, adopting AI or machine learning to automate key processes, shifting to more sustainable manufacturing methods etc.)

- Or continuing work that requires a shift in skill or mindset? (service-centric practices to improve customer experience etc.)

- What work has been critical to our success to this point, but will make a smaller contribution in the future? (operational excellence in retail stores, when future growth will come from on-line channels etc.)

- What work must we continue to excel at to sustain our position?

Several of these questions will be missed by extrapolating forward from the current situation.

The ‘Future-Back’ approach to Strategic Workforce Planning developed by Jill Foley, Managing Partner at On3 Partners helps leadership teams identify future capabilities by following a structured, ‘demand led’ set of questions which start from the strategic aims of the business.

Future-Back Model

North Star:

- What are our ambitions for the business?

- Why are they important? What does success make possible, that otherwise would not happen? What will happen if we are not able to realise our ambitions?

- What does success look like in the future?

Goals:

- What are our strategic goals and priorities? (both qualitative and quantitative)

- Put another way – what are the measurable milestones on the journey towards reaching our North Star?

Imperatives for success:

- What are the conditions we need to create to ensure that we can deliver our goals?

- What do we need to do to create those conditions? What are the things we need to initiate, change or fix for success?

Core work:

- What’s the work we need to do brilliantly to deliver those imperatives?

- How does all of this change the ‘graphic equaliser’ of what is important, i.e. which activities should be ‘dialed up’, and which ‘dialed down’?

From here you can start to discern the scale of the difference between future work and current capabilities. See our full report for more information on the application of Foley’s model.

Facilitating the conversation around strategic capabilities

While other elements of SWP are likely to involve large amounts of data and analysis, the approach at this stage is more around taking a high-level view of the future blueprint and identifying the major areas where detailed analysis and planning is required. Generally this can be achieved through discussion and facilitation. HR will need to take a consultative approach, involving conversations with key leaders and facilitated sessions to tease out the issues around what is required to enact the strategy. The outcomes of this stage are more likely to involve qualitative descriptions of macro changes required and orders of magnitude rather than absolute numbers.

Strategic Talent Mapping – from strategic capabilities to critical roles

The next stage, having identified the organisational capabilities required to deliver the strategy, is to translate this into talent requirements. One element of this is to define the critical roles that are needed to drive execution.

Organisations often confuse the size of a role or its position in the hierarchy with its criticality. In fact, the roles that are pivotal to future success will often be small (e.g. dealing with emergent challenges that have not yet reached scale) and might sit several layers below the exec (e.g. the teams developing the digital assets that will transform the customer experience).

Critical roles are those that create outsize value and contribution to business outcomes and sustaining competitive advantage. Correctly identifying and investing disproportionately in these roles should lead to better organisational performance.

There are numerous definitions of critical roles. Typically these include:

- Value creation. Value can be financial (e.g. sales) or qualitative (innovation, customer satisfaction).

- Strategic impact. Roles that make the greatest contribution to the organisation’s competitive advantage, core capabilities, or future strategy.

- Risk. This might include roles that are high risk because appointing the wrong person could damage business performance, reputation.

- Scarcity. Difficulty in hiring or developing.

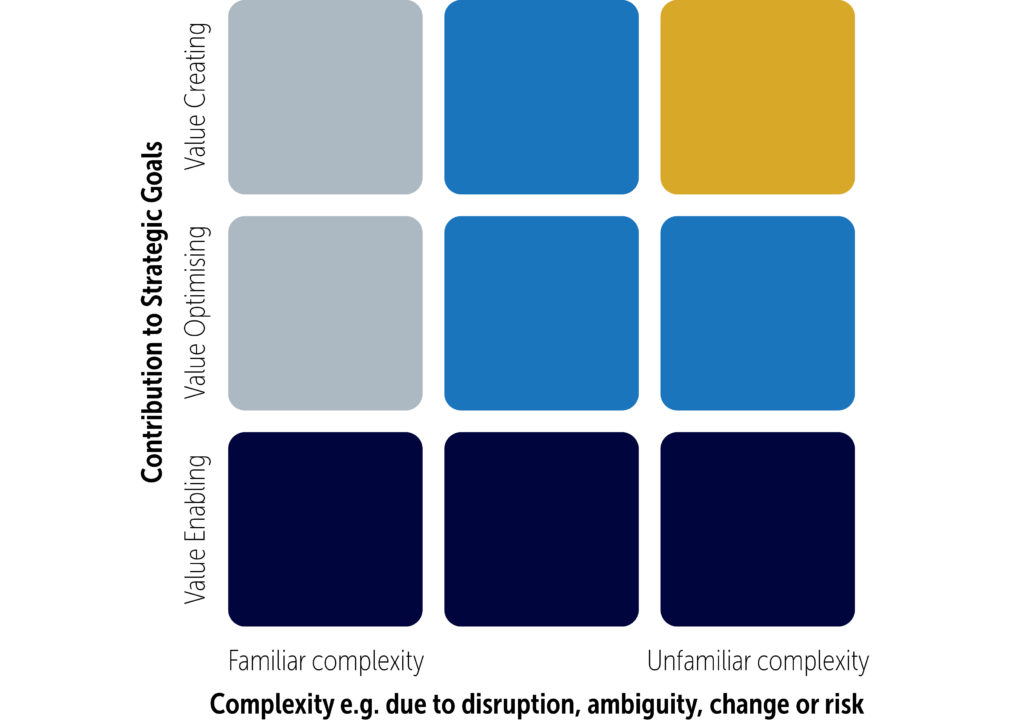

Mapping Value and Complexity

Mapping Critical Roles

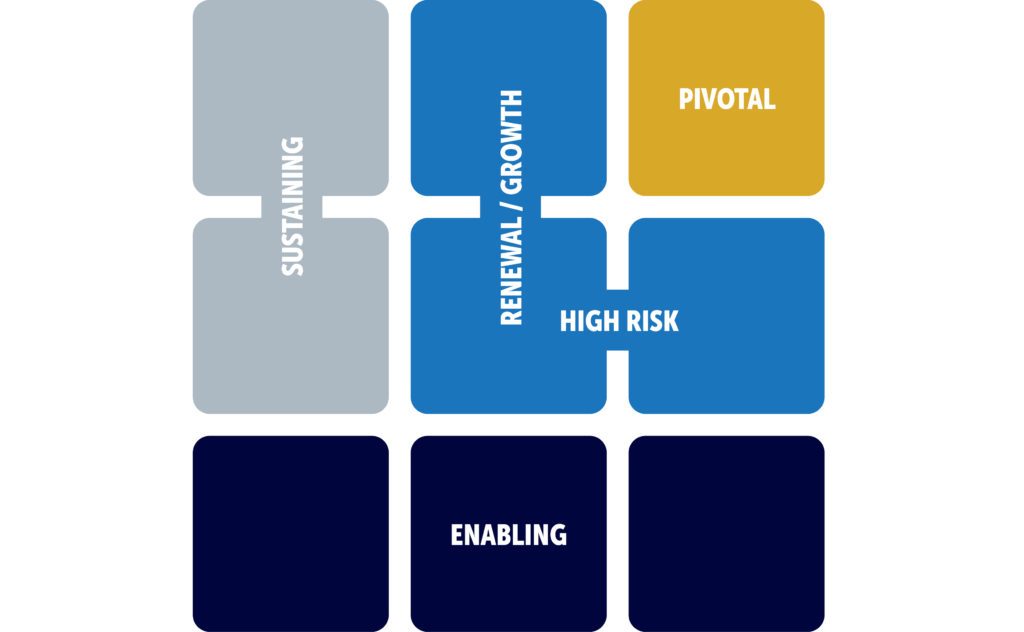

The two grids above can be used to identify critical roles based on their contribution and complexity. Foley’s approach leads organisations to distinguish the following categories of roles:

- Pivotal: game-changers, instrumental in creating future value. Success will have a disproportionate impact on future performance.

- Renewal / High Risk: roles that are concerned with changing the business for growth or to improve effectiveness and performance.

- Sustaining: concerned with ‘mature’ work where there is a clear blueprint for success. Often the biggest roles in terms of scale and resources and typically attract leadership attention because they deliver short term performance.

- Enabling: deliver the work that safeguards or enables the wider business to operate effectively.

By segmenting roles in this way, organisations can develop insights about where future success may be at risk which then informs talent management priorities. It can also inform the way that leaders match talent to value by choosing the right person based on the value contribution, scope and complexity of work. Organisations often make the mistake of placing their most talented leaders in their biggest roles when, in fact, their skills and experience may yield greater benefit by putting them in smaller, but more complex and challenging pivotal or growth driving roles.

2. WHAT INTERNAL CAPABILITY DO WE HAVE?

This stage involves understanding the current workforce and how it is changing in order to assess the availability of people to meet future demand.

This means looking at factors including:

- A baseline of the current size, location, and profile of the workforce (e.g. skills, length of service, demographic information, diversity data).

- Job or skills families and skills levels. Skills may include both generic skills which apply to the whole workforce, leadership or management skills, and technical or job-specific skills. See Sidebar opposite.

- Expected major flows both in and out – turnover patterns, retirements, anticipated restructurings, internal moves, vacancies.

- Talent management information – succession plans, internal talent pools, anticipated cohort recruitment such as graduates. These all provide information about the future internal supply of talent. For example where there is good succession cover, where there are gaps that need addressing through targeted talent interventions, where there are risks.

- Career paths and promotion information, which shows the nature and speed of movement in talent pipelines.

- Resourcing mix – balance of external vs internal resourcing for critical workforce groups, which is important in terms of understanding future supply options.

This stage of the process can be data-heavy and require data analysis capability in HR. However, by narrowing down the analysis to the strategic capabilities and talent identified in stage 1 above, the effort can be focused on the parts of the business and workforce where the greatest shifts are anticipated.

3. WHAT DOES THE EXTERNAL LABOUR MARKET LOOK LIKE?

Assessing the future shape of the workforce and potential workforce risks includes building a picture of the external supply of talent in the timescales required to fulfil the business strategy.

Relevant external market information would include:

- Changes in the working population in the markets in which the company operates. The shift to remote working seen in the pandemic may mean that companies will benefit from access to broader talent pools in geographies where they do not have operations.

- Understanding the main competitors for critical talent and potential new competitors. Is competition for that talent likely to increase or decrease?

- Likely future shortages or surpluses of key skills in current and future labour markets.

- Output of the education system in terms of subject, level and type of qualifications and quality of skills.

- The impact of innovation or automation. Is technology becoming available that will allow work to be wholly or partly automated? Will that result in demand for different skills?

- Alternative sources of supply, such as outsourcing, contingent workers or acquihiring (buying a company primarily for the skills and expertise of its staff rather than its products or services).

- Pools of workers currently working in other sectors who could be redeployed.

- Industry trends and the impact of regulation.

- Changing assumptions in the working population, for example around diversity, workplace culture, and environmental or social impact.

Examining these and other relevant factors helps build a picture of where the biggest changes in the labour market are likely to occur, which might require the organisation to develop different resourcing strategies.

Modelling and matching supply and demand

Once the organisation has developed a point of view on the capabilities needed to deliver the strategy and examined data relating to the internal and external talent supply, it should be possible to develop models to match supply and demand, assessing the gaps between what the business will need and its potential future workforce supply. Sometimes this will be obvious – we need a lot more of X and it’s hard to find – and will not require detailed modelling.

4. WHAT’S THE GAP?

The purpose of this stage is to identify gaps between future need and current supply and highlight the areas where action may be needed. This step may consider multiple timeframes, setting out when gaps are likely to open up, and allowing action to be phased in line with anticipated demands.

Gap analysis can be done both at the level of individual roles or workforce groups. Focusing on workforce groups allows planning for cohort-based recruitment and development, for example setting up an apprenticeship scheme to develop cyber security expertise.

Looking at critical roles, the grid in Figure [ ], can be used to compare the cohort of current and future leaders with the critical roles required to execute the strategy. This can help determine where the succession pipeline for key roles is thin, which talent pools need to be developed, or where individuals may need to be given developmental assignments to prepare them for a destination role.

5. WHAT ARE THE CRITICAL RISKS?

A key aim of a future-back process such as SWP is to identify the few critical things that will trip up the business if it fails to take action, that otherwise might have been missed by projecting forwards from operational plans.

This step involves reviewing the gap analysis through the lens of risk. Where is our strategy most at risk if we fail to address the gaps effectively and in good time? Risk is not just about the size of the gap – it is a combination of the size of the gap, how critical it is to strategy execution, and how difficult it will be to close the gap. Focusing on risk is an exercise in prioritisation: helping narrow down all the possible actions to those which are absolutely necessary to achieve a minimum level of capability to sustain the business, or which are most critical to accomplishing the strategy.

6. HOW DO WE FILL THE GAPS?

Having identified the major gaps and risks to strategy execution that need to be addressed by the SWP, the next stage is to formulate an action plan. This stage forms a bridge between the business strategy and people strategy/plan. The process of SWP does not necessarily result in a single planning document, but should feed into other business and people plans. There may be different plans covering each of the outcomes that needs to be delivered by the SWP, and each plan may have multiple workstreams running over several years.

In practice this is often the most complex and demanding of all stages. The work required is not just about putting plans together, it requires securing commitment by the business, both in terms of funding and effort to implement those plans. As our survey shows, translating plans into action is one of the most significant barriers to successful SWP in practice.

While some actions – recruitment and training – may be obvious, there may be other deeper organisational issues that need to be tackled. For example, developing a new line of business might require changes to the business operating model, the organisation culture may need to be refreshed, or people processes may need to be modified to better meet the needs of critical talent segments.

When considering the options available to address gaps and risks identified through SWP, it is useful to consider a range of possible actions. These include:

- Buying in talent through external recruitment.

- Growing talent internally through both formal on-the-job skill and career development, and deployment of people through developmental experiences.

- Actions around longer-term development of talent pipelines and career development.

- Create talent transition pathways (redeploying, re-skilling) to smooth out internal demand curves or redeploy people from parts of the business where demand for talent is reducing.

- Improving retention and engagement, particularly for ‘leaky’ parts of the talent pipeline.

- Increasing workforce flexibility through ‘borrowing’ talent from the contingent workforce – temporary and agency staff, self-employed contractors, and consultants.

- Developing differentiated EVPs to attract and retain new skills or attract different talent segments.

- Automating, redesigning or outsourcing work to meet changing business needs more effectively or reduce demand for workers. Specialists in SWP recommend taking a ‘total workforce’ perspective. This means analysing the work, its design and how best to get it done, rather than jumping straight to recruiting permanent positions in the workforce.

- Targeted mergers and acquisitions.

See our full report for more detail on potential actions arising from SWP and relevant case studies.

7. HOW DO WE EVALUATE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE PLAN?

The final stage of the process involves setting up mechanisms for evaluating and improving the practice of SWP and monitoring the implementation of actions arising from the plan.

Our survey found that evaluation is not a common feature of organisation practices around SWP. Less than a fifth of respondents (19%) say they evaluate the effectiveness of their Strategic Workforce Planning.

Evaluation should include both quantitative measures of the effectiveness of SWP and qualitative analysis, which enables those responsible for SWP to determine whether key stakeholders value the outcomes of the process and whether the actions identified in the plan are being followed through.

Evaluation might involve asking stakeholders questions such as:

- What do key stakeholders think about the results achieved relative to the costs incurred or effort involved?

- Did we implement the actions agreed in the plan?

- What impact did these actions have on business outcomes and key metrics?

- Do we regularly revisit assumptions and update plans accordingly?

- Do we communicate the results of SWP to those people in the organisation who need to know about them?

- How can the process of SWP be improved?

Overcoming the Barriers to Successful SWP

Our research has shown that, while SWP is an essential tool for HR to support the business in delivering its strategic objectives, in practice it’s hard to implement successfully. Most organisations that have reached a level of maturity in SWP have a history of failed attempts and have had to experiment with different approaches in order to develop a methodology that works for their business. In this section, we explore the barriers to successful implementation of SWP and look at practical solutions to some of the challenges faced.

BARRIERS

Our survey asked respondents to rate various obstacles to successfully developing SWP capability, asking to what degree each was a barrier in their organisation. The top barriers related to:

- The process being too short term or operational rather than strategic

- A lack of quality people data, particularly with regard to the skills profile of the workforce

- A lack of analytical capability in HR

- Not having a clear process for SWP, or the process is insufficiently flexible to take account of changing business requirements

- SWP process not being well enough integrated with business and financial planning

- Failing to take action in the organisation to address the issues identified.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Our research highlighted a number of ways in which organisations can overcome the common barriers to success and practical considerations in designing an approach to SWP that’s right for their business.

Positioning SWP as an essential part of business planning

It is essential that SWP is positioned as integrated with, not separate from, the organisation’s strategy development and business planning processes. It should be aligned with the business planning cycle and run to the same timeline. One benefit of this approach is that it elevates the consideration of people and organisation, making it an essential element of developing the business strategy. We recommend starting with the big strategic questions facing the organisation, or the critical risks to future success. This is where SWP can have greatest impact on business outcomes.

Stakeholder engagement

Business leaders need to buy in to SWP and engage in the process. While the process itself may well be designed and driven by HR, business leaders must also own the outcome, particularly when it comes to taking action on the plan’s recommendations. It’s important to be clear about who is the customer for SWP, and engage key stakeholders early in the process to get them on-side and to understand issues in their area for which SWP may offer a solution. SWP can be positioned as a way of helping key stakeholders have an earlier view of the people implications of the business plan.

Employees as stakeholders

Another key stakeholder, often overlooked, is the workforce itself. Our research found only 3% of organisations have a process for communicating the outcomes of SWP to the whole workforce. This is a missed opportunity and will become increasingly important as companies look to reskill and redeploy people whose roles are replaced by technology. Consider how to communicate the outcomes of SWP to the workforce. How can you make employees aware of future skills the organisation values? Can you signpost employees to relevant career opportunities and learning resources? Should you reward employees for developing skills that will be critical to the organisation’s future success?

Scope – whole workforce or critical capabilities only?

One of the reasons SWP can fail in organisations is, rather than focusing on a few business-critical elements, it tries to cover too much. Some interviewees shared that they had experienced attempts at SWP that had failed because they tried to ‘boil the ocean’. Some organisations take a project or issue-based approach to SWP, or focus on issues that cut across multiple parts of the business, such as the impact of technology. We recommend starting small and building up from there – don’t expect to tackle the whole workforce at once. It can be helpful to start where the energy is – perhaps working with a supportive business unit leader or focusing on a specific job family. Pay particular attention to workforce groups that are strategically critical to business performance and difficult to resource. These often present the greatest risk to the organisation’s ability to deliver its strategy. It’s important to look at demand and supply both in terms of numbers and the skills people will need. This means behaviours and attitudes as well as job-specific knowledge, qualifications and experience.

Take a total workforce approach

This means considering not only direct employees but also contractors, ‘gig’ workers and opportunities for improving productivity and automation. Focus on the work that needs to be done, and skills that need to be developed, not just jobs. This opens up options in terms of automation, outsourcing or engaging the contingent workforce. Include job and work design in the analysis.

Developing the capability for Strategic Workforce Planning

It’s important to clarify who’s responsible for delivering SWP and make sure they have the tools and resources they need. There should be at least one person in HR with in-depth understanding of workforce planning methods, confidence in generating the evidence-base for decisions, and the ability to work across silos in HR. SWP is often one of the more underdeveloped muscles within HR, and it might be necessary to upskill HR leaders or others who are expected to run the process. Those who are responsible for SWP both centrally and locally (eg HR Business Partners) need a mix of technical expertise – specific workforce planning skills – and broader skills such as the ability to work with others in the business. These include business understanding, technical knowledge of SWP methods, data analysis and communication, and consulting and OD skills. It’s also important for business leaders and HR professionals to have a workforce planning ‘mindset’, which might include understanding the business-specific ways in which people can enable business performance and present risks, and a continuous awareness of how workforce demand and supply, both in terms of numbers and skills, will need to change over time.

Planning for uncertainty

Some organisations and HR professionals use uncertainty as a reason to avoid or delay SWP. However, workforce planning was developed by statisticians who built ideas of uncertainty and risk into its methods, and organisations need to adapt their approaches to SWP to deal with uncertainty. Some of the common approaches used to plan for uncertainty and increase organisational agility are set out in Figure [ ]. These include building ‘what-if’ questions into routine planning, developing contingency plans around medium-term plans as a practical way of sifting business risks and deciding which ones to address, and developing a range of scenario plans to analyse factors which have the potential to have larger-scale and longer-term impact. Businesses can also use adaptive planning which builds uncertainty into how decisions are taken – plans are still made, but regularly adjusted to take account of changing circumstances. Our full report contains a chapter exploring how to develop approaches to SWP that account for uncertainty.

Conclusions

- Although it has become increasingly difficult to plan ahead, the Covid-19 pandemic has advanced the cause of Strategic Workforce Planning, as organisations have seen the value in being able to evaluate the feasibility of different strategic options, strengthen links between business and people strategy, and work out what’s required in terms of people and organisation to implement strategic plans. We expect restructuring post-Covid to lead to even greater demand for this skill.

- SWP is a good way to develop positive organisational habits around taking a pragmatic view of what it will take to accomplish the strategy, challenging assumptions, mitigating risks, and seeking evidence to support a chosen course of action. It can provide a basis for decisions regarding deployment of the workforce and future investment in skills, technology and leadership capability. Reflecting on the big strategic questions and exploring the feasibility of different strategic options can help improve the quality of thinking around strategy. SWP is as much a mindset as a methodology or series of actions.

- As well as being a key deliverable for HR, it’s an opportunity for HR to demonstrate value by influencing the organisation’s strategic direction. It can be a way of getting HR more involved in strategy discussions and getting closer to the increasingly important risk management function in organisations. It can also help HR increase its delivery credibility. By making sure HR is involved in determining the actions and plans it will have to execute, it increases the chance of HR successfully delivering against those.

- However, SWP is difficult to do well. It requires a clear strategic direction, a coherent methodology, deep strategic, commercial and analytical skills in HR, strong engagement by business stakeholders and persistence to drive analysis through to action.

- SWP needs to adopt a ‘future-back’ orientation – starting with where the organisation is heading and identifying the steps required to reach that destination. It also needs to focus on the work to be done and the capabilities that need to be in place – not simply narrowly focusing on jobs.

- SWP also needs to link to practical action in the recruitment, development and deployment of people, and where appropriate in areas such as work design and reward. Make sure there is a process for following through on actions and mitigating risks identified in the plan and keeping it up to date as circumstances change.

- SWP needs to look both externally – understanding the changing business context and labour market – and internally at the current state of the workforce and future needs.

- It’s essential to position SWP as an integrated part of business planning, not run as a standalone HR process.

- It’s also important to build adaptability into the process of SWP: being able to test different scenarios and revisit the plan quickly as circumstances change.

MEMBER LOGIN TO ACCESS ALL CRF CONTENT