Future of Work and People Strategy

HRD Briefing 2021: The World of Work in the 2020s

In 2020 we experienced unexpected disruption which has affected the entire world economy. However, the forces that were affecting employment before the pandemic haven’t gone away. These underlying trends, combined with the scarring effects of the pandemic, will shape the global labour market over the next five years. We believe the following factors will have the most significant impact on employment.

AN AGEING POPULATION

The median age of the global population is rising. In most countries, the working age population will shrink as a proportion of the population over the next decade. In some economies it will shrink in absolute terms.

- Working age (15-64) share of the global population peaked in 2014 and is now on a downward trajectory (World Bank)

- Proportion of the workforce aged 50-64 rose from 20% to 28% between 2000 and 2015 (Mercer)

- Ageing process is most advanced in North America, Europe and Japan but is taking place at speed in some Asian and Latin American economies e.g. Brazil, South Korea, Thailand

- Global nature of this phenomenon means immigration will only be a short-term fix

“We are not just looking at a war for talent, our research indicates that there will be a labour

Mercer

shortage – quite simply a shortage of people available to do the work.”

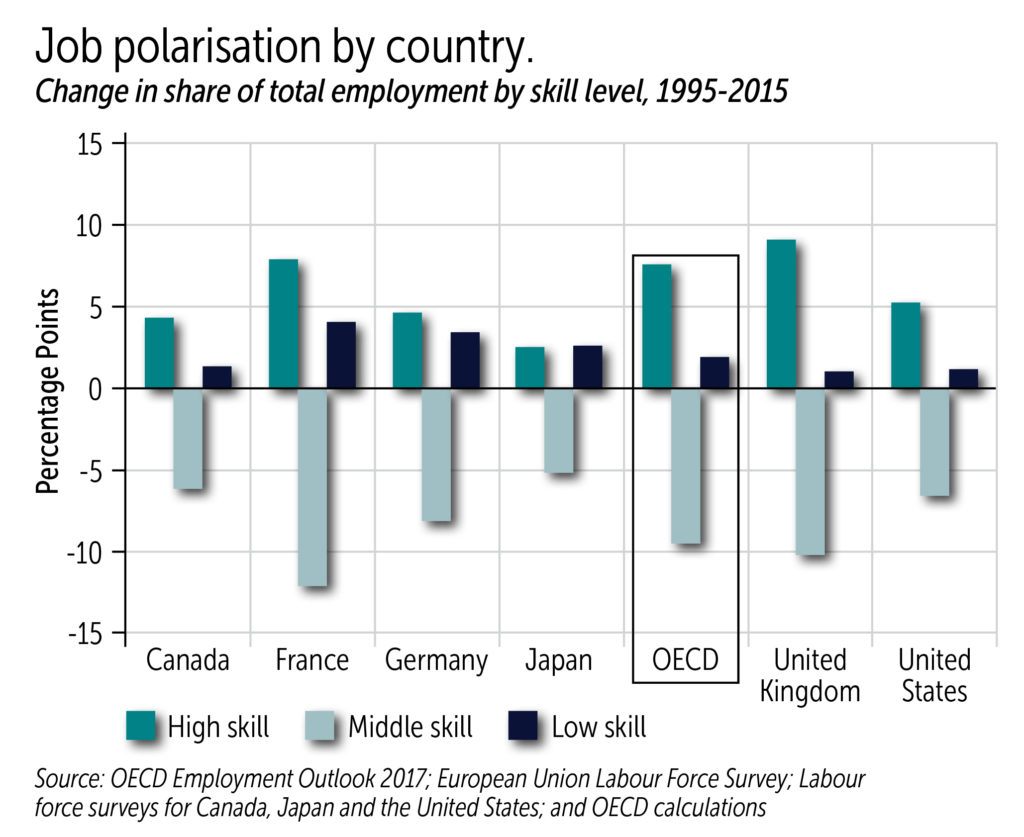

A MORE PROFESSIONAL WORKFORCE

- Across the high-income economies, the proportion of the workforce in professional, managerial and technical roles rose from 30% to 40% over the last three decades

- Over the same period, the number of workers in clerical and skilled manual roles declined

- This ‘job polarisation’ process looks set to continue, as the mid-tier jobs are populated by an older age cohort and are likely to be significantly affected by automation

- The impact of Covid-19 may speed up this process, as more companies need technical skills to help them shift to new ways of working

EMPLOYMENT RATES ARE LIKELY TO GRADUALLY, BUT NOT COMPLETELY RECOVER

- Most advanced economies saw record or near-record employment rates in the late 2010s, driven by increasing female workforce participation

- Male employment rates have declined since the 1980s, reflecting the changing structure of the economy

- The impact of Covid-19 on employment levels is likely to be severe in the short-term – the OECD forecasts a rise in unemployment from 5% to 9%, rising to 12% in the event of the second infection wave we are now experiencing

- The longer-term impact is difficult to assess – the OECD expects a gradual recovery; the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts a return to near pre-pandemic employment levels by 2024-25

SKILLS SHORTAGES LOOK LIKELY

- Retirement of the 1960s baby bulge will see large sections of the population lave the workfroce, taking their skills with them

- The IMG warns that it is unlikely that many of those displaced by automation will be able to re-skill quickly enough

- Evidence of effective re-skilling is scant – workers are slow to change industry or occupation and training makes little difference to their propensity to do so (Resolution Foundation)

- Displaced workers without degrees are more liley to move into lower skill jobs than to re-skill (OECD)

- Many economies may therefore find themselves with a simultaneous rise in unemployment and skills shortages at the same time

PAY IS IN THE DOLDRUMS

- The OECD described the pay stagnation of the 2010s as ‘unprecedented’

- Average pay levels have fallen further in most countries – where they have risen it is the result of low-paid workers being completely laid off

- OECD forecasts continuing pay stagnation, hitting low paid, part-time and self-employed workers hardest

- According to the UK’s Office for Budget Responsiblity forecasts, average annual earnings will not return to 2007 level in real terms until 2026 – two decades of pay stagnation

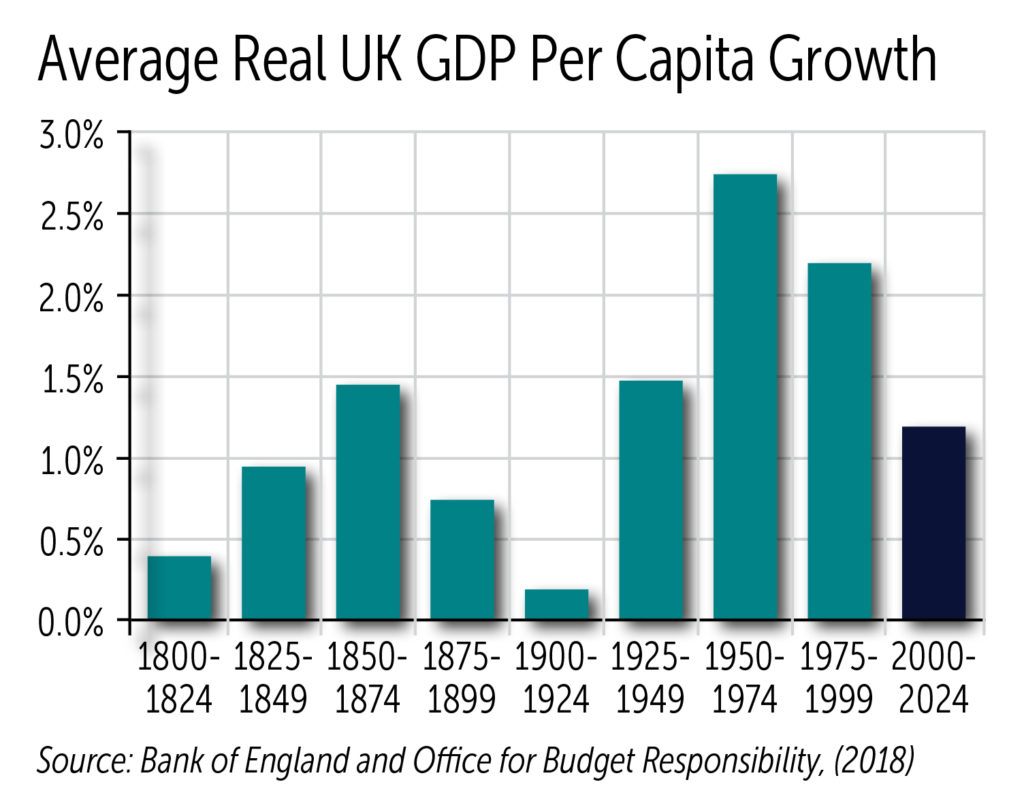

PRODUCTIVITY

- Recovery in the advanced economies was slow after the 2008 financial crisis

- UK per capita GDP is on course for 1% annual growth this quarter century, compared with 2.5% over the previous two

- Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the IMF and OECD were warning about a prolonged period of lacklustre productivity, described by the FT’s Chris Giles as ‘synchronised stagnation’

CONCLUSIONS

In our view, the most serious labour market challenges facing companies are the need to shift business models and ways of working in response to changing consumer behaviour and finding the skills to make that happen. In the light of demographic headwinds, increasing demand for technical skills and a hitherto poor record on reskilling, we believe the IMF’s warning from 2018 of simultaneous skills shortages and high unemployment looks likely. Investment in employee development and the organisational ability to deploy technology is every bit as important as the technology itself. Governments and companies should focus on this as a matter of urgency.

PRACTITIONER VIEW

In the context of Puma Energy, a mainly emerging market company the ‘current’ workforce trends are supplemented with an ‘evolving’ trend namely a transient, remote and gig economy and workforce for ‘remote or hybrid’ roles.

- We have to completely change the paradigm of permanent, full-time, I-work-for-one-company-only approach

- We have to be able to attract and ultimately have talent performing from ‘anywhere’

- We have to rethink what is ‘core and contingent’ capability

on a global as well as local basis

Specifically the energy transition for us will require:

- ‘New-skilling’ a vast no-skills and low-skills workforce in our emerging market talent pools. We predict a positive emerging market dynamic which is unlikely to mirror the perceived OECD trend that displaced workers without degrees are more likely to move into lower skill jobs than to re-skill.

- Activating a much larger part of the female talent pool of the emerging market talent pools.

For this to become real, we need a major call to action in order to combine industry, education and government collaboration and align interests and priorities.

This article is part of our 2021 HR Directors’ Briefing Paper. Continue to the next article: Future of Talent.

MEMBER LOGIN TO ACCESS ALL CRF CONTENT