Business and People Strategy

HRD Briefing 2022: Redesigning Retirement – The Case for Change

CRF’s 2021 research report, Building a Future-Fit Workforce — Reskilling and Rethinking Work, examined the landscape against which the future of work will evolve. This article takes an in-depth look at one of the key issues identified in the research – the challenges posed by an ageing and shrinking workforce.

By 2030, the percentage of workers aged 50 to 64 will increase dramatically. In most developed nations, the increase will be somewhere between 27% and 50%, compared with just 10% to 15% in the last century. We are now living around 10 years longer than our parents on average and 20 years longer than our grandparents. At the same time, many countries are struggling with worker replacement ratios because of shrinking birth rates which all lead to labour shortages and mean problems for employers.

The world has changed forever since COVID-19 hit in parallel with these demographic challenges to workforces. Mercer’s Global Talent Trends study 2020 showed that 97% of C-suite are concerned about high performers in their organisations taking early retirement. Paradoxically 95% of C-suite are also concerned about the lack of movement in senior roles. Given these two concerns, why is it that only 33% of employers have an active programme in place to manage retirement?

Turning to employees’ concerns, around 77% of employees expect to continue working past retirement age, many for financial reasons. On average, people are running out of money in developed geographies some 8 to 20 years before they die.

This position is worsening, and we see a global pension gap expectation (the gap between actual savings and the amount of money people will need) accelerating to $400 trillion by 2050. Furthermore, not all pensions are created equal. The gender pension gap exists in virtually every retirement income system around the world, with Japan having an almost 50% gap while Estonia’s gap is less than 5%. The average for the OECD is 26%. By today’s values, on an average wage, this gap can represent $8,400 per year in the US and £6,000 per year in the UK. There are ways to fix the gender pension gap but they are a complex web of cultural, social, employment and pension design problems and it will take decades.

These new realities mean we need to redesign retirement to be fit-for-purpose in the 21st-century. We go as far as to say the word retirement is already retired.

“An active, flexible retirement programme can support employers and employees alike with the challenges that we are facing in a modern workplace, and go some way to fixing inequalities too.”

Increased longevity has created a new stage of life – ‘bonus years’. Financing the 100+ year life means balancing traditional short-term financial pressures with the need to manage medium-term risks and prepare for long-term financial resilience. Inevitably, this means taking a new broom to ways of working and earning as we may all have to do this for longer to fund the bonus years.

The pandemic battered investments, jobs and pensions; we saw people drawing early on their pension funds to get immediate cash, and many early retired altogether. The combined stresses put on healthcare systems, the ‘race to reskill’ to meet the changing needs of work, and the overnight pivot to remote working – all of these contributing factors have accelerated the move towards creative new flexible working and redesigned retirement models.

Progressive employers are already experimenting with pilot programmes that enable the right conditions for employees to thrive, for example:

- Phased and flexible retirement programmes are becoming more commonplace. These are best facilitated simply by an extension of flexible working into all stages of life including later career and retirement.

- In some cases, extreme skills shortages produced by the demographic challenges mentioned earlier mean that employers have to incentivise workers to stay on in late career. For example, a flexible retirement programme may mean a gradual shift from full-time work to full-time retirement over a period of, say, three years. The payment of pension contributions on full-time salary even though employees may only be working two or three days a week is a good example of this incentivisation.

- Creating new, flexible employment contracts that enable people to work on a project-by-project basis is also becoming a more commonplace solution, as is offering holistic ‘midlife check-ups to develop a personalised life plan based on your own health, finances, job skill needs and network.

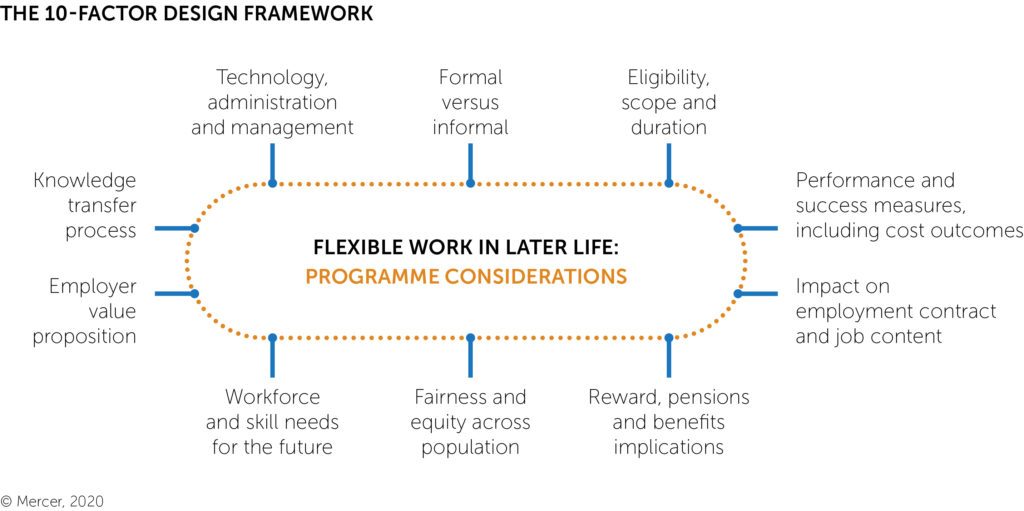

- Mercer designed a 10-factor framework to help employers understand the programme considerations needed to implement these types of approaches. An outline of the framework diagram is shown below:

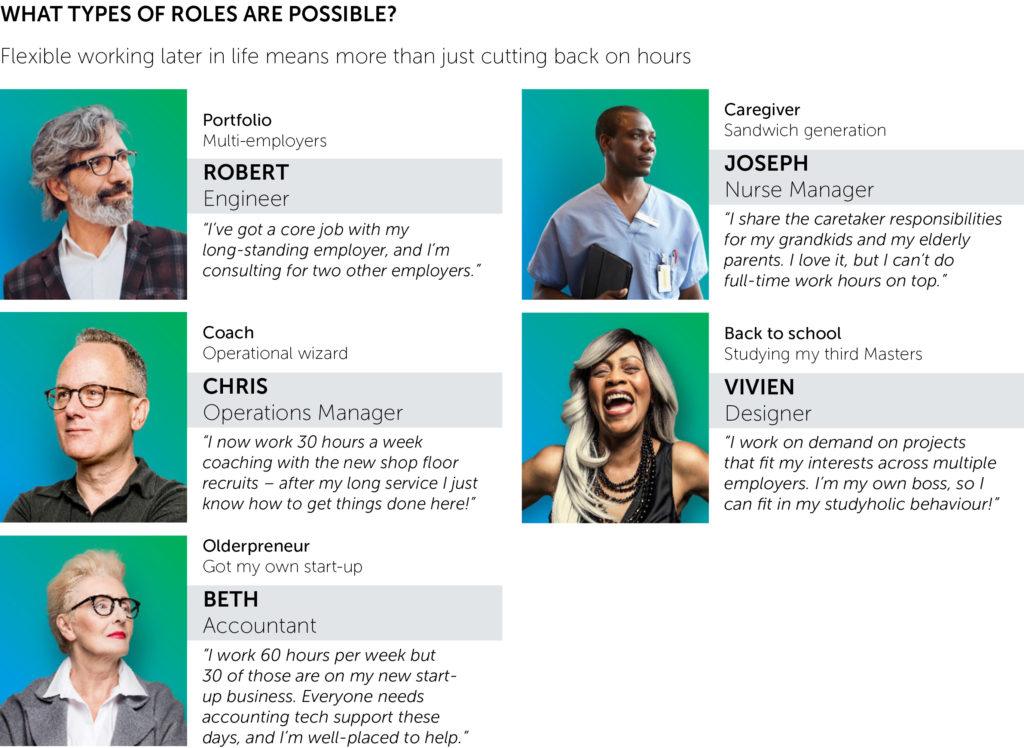

Flexible working in later life means more than just cutting back on hours:

All of these new situations can be accommodated in a flexible employment model with some reshaping of the usual elements. For example, a traditional full-time employee will usually enjoy a base salary plus employee benefits and potentially a bonus. Compare this with a contractor who will usually just earn a day rate and you can see there is an obvious gap for a new approach – a hybrid model – in between these two. Our ‘Contractor Plus’ model provides just this, offering a day rate, plus access to social protection benefits for key life events such as health, pension and death as well as ongoing training to enable people to upskill. Employees and employers both benefit from the improved flexibility:

- The employer can retain key experience where needed, transition more smoothly to job redesign as jobs and skill needs for the future change, and potentially save costs from reduced recruitment and onboarding time outages.

- The employee can continue to work and earn, have access to social protection benefits such as pension, healthcare and risk insurances, and thus be better equipped to meet short-, medium- and long-term financial resilience.

We also see new employment models which incorporate gradual pension drawdown to supplement lower pay rates as working time reduces. These models can take people successfully through into a more financially sustainable, longer, and phased retirement.

Given that COVID-19 has enabled the great flex work experiment, perhaps the time to test out new employment models is now.

PARC will be exploring the topic of ‘Retirement Income Strategy – Does Your Company Have One, Does It Want One?’ at their event in March 2021. Further details here.

This article formed part of the HR Directors’ Briefing: Scanning the Horizon: Trends and Issues in 2022. View the full Briefing here.