Talent, Leadership and Learning

Speed Read: Resourcing – How HR’s Core Competence Is Evolving

SPONSORED BY:

A priority for executive leaders today is to prepare their businesses for the digital age. Attracting and retaining the right talent for digital success is a key challenge, with many businesses competing for the same scarce skills, including hard technical skills and the soft skills needed to translate technology into usable products and services. The search is further complicated by changing worker expectations. Employee loyalty is no longer a given – encouraged to take charge of their careers, more people are looking outside their organisation for promotion. Most employees are now passively seeking job opportunities at all times, and self-employment and entrepreneurialism are increasingly popular. Thus, the search for talent is at its most challenging at the same time that the rewards of capturing the best talent are at their greatest.

Resourcing, one of HR’s core competencies, is rapidly evolving too, as new technologies emerge, competition for scarce skills increases, workers’ expectations change, and the direction and culture of businesses themselves rapidly change. In this context, it is critical that HR professionals build a strategic approach to resourcing – a resourcing strategy closely aligned with the business strategy can help drive the business to success in the face of today’s and tomorrow’s challenges.

The purpose of this Speed Read – a summary of the full CRF report Resourcing – How HR’s Core Competence is Evolving – is to examine key trends in resourcing and to demonstrate how HR can make a substantial strategic contribution by closely aligning the resourcing strategy to the business strategy. We briefly examine today’s resourcing context, introduce a CRF Resourcing Model that sets out a framework for linking business strategy to resourcing strategy, review the role of job analysis in recruitment, consider the evolution of the employer brand, and examine the latest trends in recruiting with a focus on new technologies. We conclude with recommendations for improving the practice of resourcing. While this Speed Read offers a quick introduction to each of these topics, please see our full report for more detail.

Why does it make sense to invest in identifying ‘star’ performers?

Investing in good resourcing practices can help businesses to predict tomorrow’s star performers. Why is this valuable?

Because research has found that the distribution of employee performance follows a ‘power law’ (or Pareto) distribution rather than a normal (or bell curve) distribution. In a Pareto distribution, there is a small number of ‘hyper performers’, a broad swathe of good performers, and a smaller number of poor performers; in a normal distribution, performance would bunch around the middle, with a small number of very high and very low performing outliers. The small group of ‘hyper performers’ in a Pareto distribution account for a disproportionate share of total business value. This effect is particularly pronounced in the highly complex, knowledge-based jobs that power today’s economy (jobs in manufacturing are more likely to be normally distributed).

Thus, organisations that can design resourcing processes that effectively attract and retain ‘hyper performers’ harness an important competitive advantage over competitors who lack this capability.

Building a Strategic Approach to Resourcing

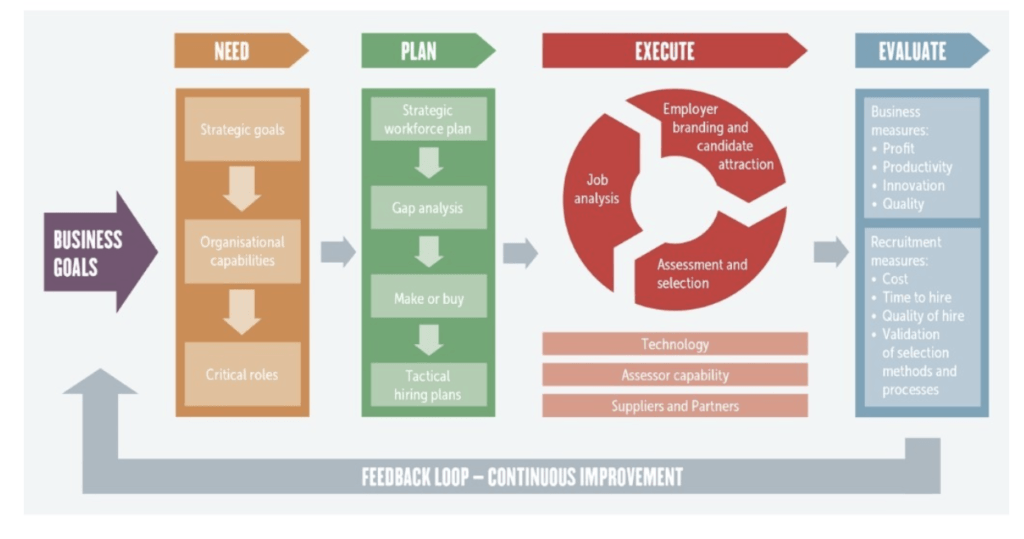

CRF STRATEGIC RESOURCING MODEL

The CRF Strategic Resourcing Model summarises our view of the elements of a strategic approach to resourcing. The model is underpinned by the following principles.

- Driven by the business strategy.

- Resourcing is an integrated system that has to work congruently with other strategic people processes.

- Rooted in science, in particular organisational psychology.

- Analysis before action.

- Clear measures and feedback loops.

CRF Strategic Resourcing Model

In Stage 1, the organisation focuses on understanding its need(s). Organisations must clarify:

- the strategic goals of the organisation

- the differentiated organisational capabilities that need to be developed to execute the strategy

- the critical roles, strategic job families and competencies that have a disproportionate impact on the organisation’s ability to build competitive advantage.

In Stage 2, the organisation builds its detailed resourcing plan, starting with strategic workforce planning to identify requirements and gaps between the current and the desired state.

Key elements of workforce planning include the following:

- Build a picture of the employment context for the organisation.

- Identify key workforce risks.

- Decide whether to make (develop internally) or buy (recruit externally) talent.

- Develop a full and up-to-date picture of what skills are available, internally and externally.

- Build future supply.

- Take a ‘whole workforce’ perspective by identifying opportunities to meet needs through outsourcing, contracting, hiring consultants, etc.

The outcome should be a set of clear priorities and an action plan that can be communicated, implemented and its progress tracked.

In Stage 3, the organisation executes its plan. There are three key activities at the core of resourcing:

- job analysis

- employer branding, candidate attraction and sourcing

- the design and execution of an effective assessment and selection process.

These activities are underpinned by essential resourcing infrastructure, which include technology (the tools that manage the recruitment process), assessor capability (what is the quality of the human judgement(s) that drive recruitment decisions?), suppliers and partners (are these relationships managed effectively?), and connections to internal talent management processes (are recruitment, onboarding, internal talent development, and succession planning coordinated?).

In Stage 4, the organisation evaluates the impact of its resourcing activities against business outcomes. Did the resourcing activities deliver against the agreed business objectives. Are assessment and selection criteria successful in predicting high performance of candidates? How can practices, processes, and methods be adjusted and improved?

What Does Good Look Like? The Essential Role of Job Analysis

WHAT IS JOB ANALYSIS AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

Job analysis tells us ‘what good looks like’ for a given position. Once the characteristics and behaviours that drive success in a role are identified through job analysis, the appropriate assessment and selection procedures for the role can be selected.

Job analysis has two principal outputs:

- Job responsibility statement: a list of the key outputs of the role.

- Job specification: the attributes required for success in the role (including knowledge, skills, abilities and other characteristics).

Job analysis has lately fallen out of fashion. Some argue that it is impossible to do in today’s fast-paced business climate, or that certain roles are too complex to be analysed effectively. Nevertheless, a systematic, data-driven job analysis is essential to successful recruitment outcomes. The analysis should look at both the technical and personality requirements of the role and should reflect the needs of the role today and in the future.

Conducting a rigorous job analysis can help to do the following:

- Identify the characteristics that distinguish the highest performers from average and poor performers, allowing you to focus selection accordingly.

- Choose the right selection tests.

- Provide evidence to defend any accusations that selection methods are unfair to protected groups.

- Provide the basis for developing structured interviews, which are much more accurate than unstructured interviews.

- Increase diversity.

HOW TO CONDUCT JOB ANALYSIS

A well-conducted job analysis typically comprises three elements:

- Quantitative data analysis. The goal is to identify through statistical analysis the elements that are necessary to perform the role and the characteristics that distinguish high performers. This requires a large sample size of similar roles, good quality historical and clear hypotheses to test.

- Scientific research on specific jobs or job families. You can tap into decades of research into the performance criteria for specific roles. Tools such as the U.S. Government’s Occupational Information Network or job profiles produced by consultancies can be valuable.

- Qualitative input from key stakeholders. The most common approach companies take is using interviews, questionnaires, and/or focus groups to ask stakeholders to identify the important criteria for success in the role. While this strategy is valuable for helping to win the buy-in of key stakeholders, it isn’t necessarily scientifically valid. To increase validity, start with a pre-determined set of criteria or questions and ask people to rank these, rather than starting with a blank sheet of paper. Then check the conclusions against the scientific literature related to job performance.

Finally, when planning job analysis it is critical to keep in mind the following:

- Job analysis is not a one-off activity. You need to review and update it as circumstances alter – when there is significant organisation change, for example, or a deterioration in the predictive validity of the assessment process.

- Job analysis is essential before recruitment takes place, but you also need a feedback loop at the end of the selection process.

The Evolution of the Employer Brand

As the balance of power between employers and candidates shifts in favour of candidates, employers are rethinking all aspects of the resourcing process, including employer branding. In this section, we explore common approaches that employers are taking to adapt their employer brands (defined as the organisation’s reputation as an employer, as opposed to its corporate or product brand) to attract the talent they need, and the implications of technology, social media and professional networks for sourcing candidates.

Our research identified the following notable practices:

- The employer brand as a source of competitive differentiation. The most effective employer brands are clearly differentiated from competitors. In practice, this means using the business strategy and the organisation’s overall competitive positioning to develop of a relevant, differentiated employer value proposition (EVP). Organisations also need to invest in understanding what critical talent is looking for in an employer.

- Building authenticity through storytelling. Storytelling is crucial to building a strong employer brand. Using case studies, personas and conversations, companies can demonstrate the authentic voices and experiences of their employees. Ideally, stories should give a realistic portrayal, i.e. highlighting both ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

- Using the employer brand to help candidates self-select. Some organisations are using new online selection tools and games to help candidates decide whether the company is right for them and, in particular, to check if the corporate culture is a good fit with their values. The objective of these tools is to encourage the ‘right’ candidates to pursue an application, dissuade the ‘wrong’ candidates from applying, and to leave everyone feeling positive about the company.

- Focusing on the candidate experience as a key element of differentiation. Companies are investing in the latest technology, such as gamification, virtual reality, and AI-enabled interviewing, to differentiate the end-to-end candidate experience and to position their organisations as exciting and forward-looking. While it’s important that candidate experience lives up to the promise of the employer brand, it is also important to keep in mind that technology cannot substitute for a strong brand aligned with a company’s values.

- Blending the corporate and employer brand. Social media is increasingly blurring the internal and external boundaries of organisations. This has important implications for recruiters, who now need to work more closely with marketing to align employer and product brands. Recruiters also need to build their marketing skills, in order to apply consumer techniques to engage talent populations.

- Building communities to engage passive candidates and build an external talent pipeline. Organisations are finding that their employer brands need to be ‘always on’ in order to engage passive candidates and build external talent pipelines. Ever more sophisticated candidate relationship management (CRM) tools and new techniques such as ‘social media listening’ are helping organisations by facilitating ongoing relationships with passive talent.

- Focus on purpose and culture. Research shows that candidates continue to look for more than money in their careers; a strong sense of purpose and a good organisation culture remain important positive differentiators for companies. In fact, purpose and culture can help organisations overcome negatives such as low pay or long hours.

- Measuring the candidate experience – assessing candidate perceptions as they go through the process. Keen to understand if their investments in improving the candidate experience at each stage in the process are bearing fruit, employers are now evaluating the employer brand at a much more granular level and at multiple stages of the process. This data then feeds into improving each stage of the process.

THE ROLE OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN EMPLOYER BRANDING

As part of our research, we conducted a content analysis of 30 leading companies’ employer brands. Our analysis revealed that large blue-chip employers have developed robust online presences, with most companies active simultaneously on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Glassdoor is under-utilised. Some companies are active on more niche social media networks such as Instagram and Snapchat. Our research finds that most companies have heeded advice to use social media channels to promote employer brand in authentic, open, and selective ways. However, many companies maintain a passive approach, simply posting content to these channels, rather than actively engaging with their audiences.

Organisations thinking about how to use social media to build or improve their employer brand might consider the following:

- Invest in ongoing active engagement with your audiences on social media channels. You might do this through deploying artificial intelligence such as chatbots to answer potential candidates’ questions, or by engaging your employees to act as brand ambassadors, participating in discussions and answering questions on social media.

- Take advantage of the unique capabilities of Glassdoor to evaluate your employer brand and recruitment process.

- Reply to reviews on Glassdoor to manage your company’s reputation and enhance the employer brand.

- Utilise the voices of your CEO or senior leaders. Thought leadership pieces on LinkedIn, short Tweets and blog posts can increase senior leadership visibility and enhance the employer brand.

- Stating your company’s commitment to diversity and inclusion is good, but showing how you are meeting this commitment is better. Use social media to highlight programmes and employee journeys to demonstrate that diversity and inclusion are part of the fabric of your company’s culture.

CANDIDATE SOURCING

Technology, social media, and cost concerns are reshaping companies’ approach to candidate sourcing. We are seeing less reliance on search agencies, job boards, and external recruiters. Instead, there is a greater focus on mapping passive talent and using new technology to source talent globally and to manage these relationships.

This changing recruitment model is putting responsibility for employer branding more firmly in the hands of recruiters and line managers who deal directly with candidates. Consequently, the capabilities required in these roles are changing significantly. People in these roles are brand ambassadors; they need to be technology and market savvy and able to represent the employer effectively in the external market.

Assessment and Selection – What and How

WHAT SKILLS AND CHARACTERISTICS SHOULD WE ASSESS?

As noted above, job analysis is critical to determine the key requirements and tasks of specific roles, the factors that drive high performance, and to identify what to measure when looking to fill the role. In the absence of a detailed job analysis, psychologists have identified generic factors that predict high performance in any role, in any organisation, regardless of level or industry sector:

- Intelligence. Intelligence is the best single predictor of high performance and career success, especially in complex or intellectually demanding jobs. This is primarily because it accounts for individual differences in learning ability – high intelligence is associated with the ability to learn quickly and in great depth.

- Certain personality traits. Certain personality traits related to social skills are correlated with high performance. Conscientiousness is the strongest and most consistent predictor of career success. Low neuroticism and extraversion are positively correlated to performance to a lesser extent. However, it is important to note that the effects of personality are more strongly mediated by the situational context than is the case for intelligence.

- Motivation. The most successful performers tend to be highly motivated to achieve work and career goals. Motivated employees are more likely to set realistic goals, work hard, persevere in the face of setbacks and learn from mistakes. When assessing motivation, it is critical to rely not on what individuals say about their ambitions and career goals, but on what they actually do to achieve them.

- Organisation context, values, and culture fit. Individuals with incompatible values often fail to adapt to a new organisation even when they have the right skills and expertise. This is true even for star performers. It is therefore critical that companies be realistic about their values and culture, so that prospective hires can be evaluated against the correct standards.

HOW TO ASSESS: WHAT TO CONSIDER IN DESIGNING A SELECTION METHODOLOGY

Choosing an appropriate assessment methodology inevitably involves trade-offs. The most accurate assessments are also often among the most costly, and highly valid tests can be subject to legal challenge in some countries on the grounds of fairness. It’s important to make an informed decision about which trade-offs you are prepared to make and the downsides associated with those choices.

The choice of method will be driven by a number of factors, including the volume of candidates, the business criticality of the role, the stage of the process, the impact on the employer brand, and current gaps and issues (for example, cost reduction pressures).

There are four key factors to keep in balance when designing an appropriate assessment methodology for any role:

- Accuracy. Are the assessment tools you are using reliable and valid? How do you know?

- Cost. What is the total cost of an assessment method, and how critical is it to the role you are assessing for?

- Candidate experience. Are the assessment tools you are using a good fit for the type of candidate that you are trying to attract?

- Fairness. Generally, ethical considerations lag behind the technical sophistication of available products. It is important to think carefully about whether you should use a particular tool, however efficient or cost-effective it might be.

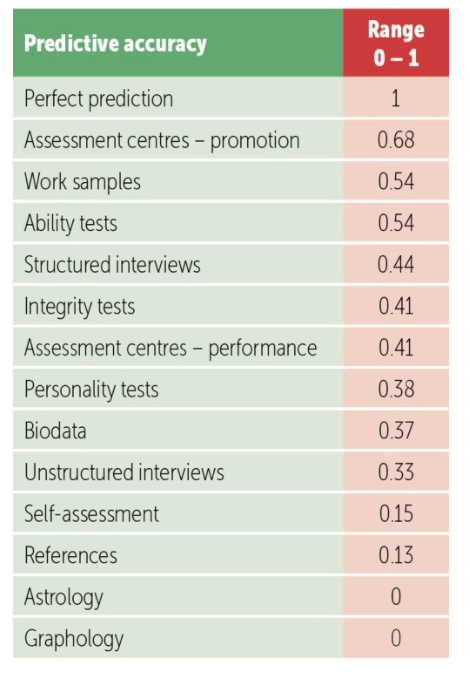

Predictive Accuracy of Various Recruitment Methods

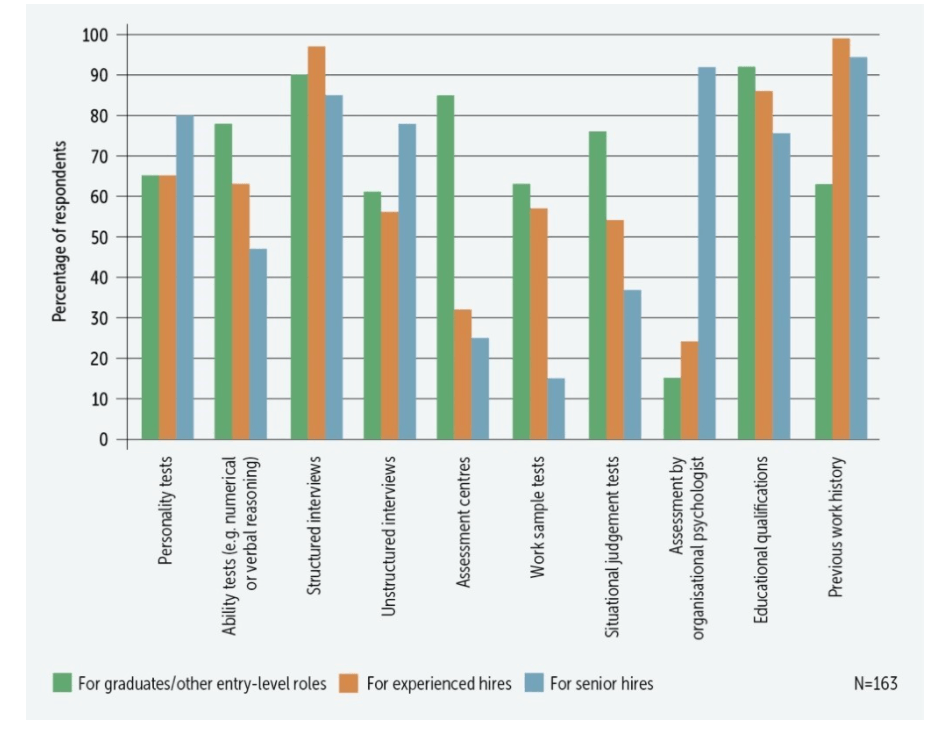

Which of the Following Do You Use Currently to Assess Candidates’ Suitability?

CURRENT ASSESSMENT METHODS AND THEIR VALIDITY

In this section, we briefly consider selection methods in common use today and consider their accuracy in predicting high performance:

- Interviews. Interviews are one of the most commonly used assessment methods. Structured interviews are significantly more accurate than unstructured interviews.

- Video interviewing. A significant recruitment trend, video interviewing can bring efficiency, flexibility, cost savings, and structure to the interviewing process. However, the quality of interaction is generally lower and it is important to keep the process consistent for all candidates in the interest of fairness.

- Assessment centres. Assessment centres are cost and time intensive but offer high accuracy.

- Work sample tests and simulations. These methods offer high accuracy and are perceived favourably by candidates.

- Situational judgement tests (SJTs). SJTs allow organisations to test how candidates respond in typical work scenarios. They have reasonably high predictive validity and are perceived favourably by candidates.

- Biodata. Short for biographical data, biodata represents all the information about a person’s background, life history, education, employment history etc. that organisations collect and analyse. Biodata has strong predictive validity.

- Gamification of assessments. The use of computer games to assess candidates is a major trend. Gamified assessments may be more enjoyable for candidates and may feel highly customised to the organisation. However, there are still many questions around how the games work, what they are actually measuring and how reliable or valid they are.

- Algorithms, artificial intelligence and machine learning in selection. Technological development that is generating much interest in the field of assessment is the application of algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to selection processes. They are driven by data, and organisations are adopting them because of their potential to make selection practices more evidence-driven and less intuitive. Applications of AI in recruitment and selection include text analysis, CV scraping, applicant sifting, facial and voice recognition, and bots. Though these methods may prove beneficial over the long term, at this time it is important to keep the following in mind.

- The technology often turns out to be less effective than expected.

- What happens inside the ‘black box’ of the application is often not well understood.

- It can be difficult to persuade recruiters to embrace new tools.

- It’s difficult to distinguish valid correlations from ‘noise’.

- The ethical implications are substantial, but development of ethical norms is lagging behind the technology.

- Depending on how the algorithms are built, there is a risk of programming in unconscious bias.

- Passive profiling. It is possible to understand, with high accuracy, a great deal of information about individuals from the digital trail they leave behind as they use the internet. By using algorithms to analyse digital behaviour such as social media interactions, the content and tone of emails, geographic location, choice of music and so on, you can build an accurate picture of an individual’s personality, IQ, political persuasion, sexual orientation and many other psychological traits. However, research shows many candidates find social media profiling uncomfortable and unfair. Over the long term, we are likely to see a shift in the balance of power between employers and employees, with employees enjoying greater data portability – that is, employees will take their data, such as personality and testing information, with them when they move from one organisation to another.

Recommendations for Improving the Practice of Resourcing

In this concluding section, we offer several recommendations for improving the practice of resourcing in organisations.

- Focus resourcing on supporting execution of the business strategy. In practice, this means:

- Having current intelligence on the availability of key talent in your markets, what that talent wants, and how to position your organisation in a way that’s both attractive to that talent and differentiated from competitors.

- Thinking about resourcing at the point the business strategy is being formulated. It needs to take into account what capabilities are required to execute it, and to what degree they already exist. HR can add value to the strategy development process by providing data and insight on the availability of talent; help the assess the feasibility of different strategic options.

- Becoming more proactive and less reactive. The foundation for this is to have a framework for strategic workforce planning.

- Being clear about where your resourcing strategy needs to be competitively differentiated. This will drive decisions about where to focus investment in building resourcing infrastructure – for example, adopting the latest technology or hiring the best-quality (and most expensive) recruits.

- Approach resourcing as an integrated, end-to-end people process. Talent acquisition needs to integrate seamlessly with other people and talent management processes including workforce planning, external hiring, internal mobility, succession planning, talent management, onboarding and people development. This is an area where organisations have scope to improve, not least because internal boundaries between different parts of HR often prevent an integrated approach. Key questions include the following:

- What do we do with the data we’ve gathered about a candidate during the recruitment process, once they join?

- Does their line manager see that data to help them understand the most effective way to manage their onboarding?

- Does the data feed into the process for setting objectives or defining a development plan?

- Does the organisation’s process for learning-needs analysis take account of assessment data?

- Do line managers get any support or advice as to the best way to motivate or manage the individual, based on what the assessment identified?

- Could we make better use of our HR systems to share this information between recruiters, line managers and HR?

- Build a robust approach to resourcing. This means the following:

- Not only building a consistent methodology for recruitment, but also ensuring it’s consistently applied. Applying a standardised process is not only fairer, but can also help organisations achieve their diversity goals.

- Using evidence to drive the process. This means using rigorous job analysis as the foundation for the selection process, tapping into the science that drives high performance in different roles, and validating after the event whether the selection methods used are most effective at singling out the highest performers.

- Investing in assessor quality. The application of robust assessment tools by inexperienced assessors is a recipe for sub-optimal recruitment outcomes. Train assessors to make good judgements and to apply assessment tools effectively, and gather data on the effectiveness of assessor decisions.

- Evaluation, evaluation, evaluation. Evaluation should answer these questions: Is the process efficient? Is it effective? Can the process be improved? Evaluation should focus on the metrics the business is most interested in.

- Build a resourcing process that promotes diversity and inclusion.Creating a diverse workforce at all levels is now a key objective for business and HR leaders alike. This is influencing how organisations hire. Helpfully, social science has identified ways in which selection decisions can be framed to increase objectivity and decrease unconscious bias. For example:

- Using the wisdom of crowds. Numerous studies have shown that taking the average of a number of different forecasts can beat the predictions of ‘experts’. Having multiple reviewers rate the same candidate is a way of bringing this insight into the resourcing process.

- Removing language from job descriptions and job postings that consciously or unconsciously deters certain groups. The words used to describe roles in your organisation send important messages about culture. For example, words such as ‘ambitious’, ‘assertive’ and ‘leader’ have been found to deter women from applying.

- ‘Blind’ recruitment. Some organisations do not ask candidates to supply biographical details so assessors can focus on gathering objective evidence. Studies have shown that the CVs of fictional candidates with white-sounding names are more likely to be invited to interview than identically qualified candidates with non-white sounding names. A meta analysis by Barrick et al (2008) found that biographical information from the applicant’s application form or CV – such as the university they attended – have a big effect on interviewer ratings.

- Machine screening. Computer algorithms can ignore irrelevant demographic information and focus on true performance differentiators.

CONCLUSIONS

We close this Speed Read with a few concluding observations:

- Attracting and retaining high quality talent is as important as ever to business success. This is an area where HR can make a substantial contribution to business strategy – both by providing talent data and insights to assist in strategy formulation, and in developing the capability to hire the key talent needed for effective execution of strategy.

- It is becoming easier than ever for companies to find and engage directly with external talent. However, candidate expectations are also shifting, and organisations have to work hard to understand what motivates top talent and build experiences that convince them to join and stay. The most sophisticated organisations invest in differentiating their employer brand from competitors’, and thereby empower candidates to make informed choices about whether it’s the right place for them.

- We are witnessing an explosion of new technology in the resourcing market, fuelled by social media, artificial intelligence and machine learning. However, we need to remember that the factors that drive a successful resourcing strategy have not changed. These include being clear about what individual factors drive success and therefore underpin what you are looking for, building a fair and robust selection process that predicts the highest performers and is consistently applied, and evaluating outcomes in order to continuously refine and improve the process.

- Technology is fundamentally altering the process of identifying talent in organisations. However, it is important to keep in mind the following:

- The new tools have not yet demonstrated validity comparable with old school methods.

- It can be easy to underestimate the limitations of new technology, or the amount of work required to get it to work properly in the context of your organisation.

- Although technology offers the possibility of making recruitment faster, fairer and more objective, it’s important that we don’t become so enamoured of the technology that we lose the human touch.

- Concerns around privacy and anonymity may constrain the implementation of some new tools and limit access to individual data.

- There is a trade-off to be made in terms of cost, accuracy and user experience. The cost of building new tools may be prohibitive, or the data needed to fuel the AI engine may put these tools out of reach for all but the largest organisations.

- Innovations in the field of assessment are predominantly focused on how to assess, whereas the more important question is what to assess.

MEMBER LOGIN TO ACCESS ALL CRF CONTENT