D&I and Wellbeing

Speed Read: Let’s Get (Beyond) Physical – Creating a Multidimensional Approach to Employee Wellbeing

SPONSORED BY:

Employee health and wellbeing is a longstanding concern among employers. At some organisations, such as Unilever, improving the quality of life of employees and their families was a founding principle. Many more organisations have invested in employee wellbeing in recent decades as its link to business performance has become clearer. Still others find that there is both a moral and a business imperative to prioritise employee wellbeing, or that it is consistent with their organisational mission.

Of course, for many organisations all these factors matter – attending to employee health and wellbeing can positively impact business performance, may be a founding principle or closely tied to the organisational mission, and may simply make good sense in a social and political context that increasingly demands businesses be accountable for their broader social impact.

However, the employee health and wellbeing agenda has tended in the past to be narrowly focused on employees’ physical health. This is not surprising, as some of the earliest efforts to improve employee wellbeing were focused on health and safety in predominantly manufacturing-based economies – efforts that have been very effective in reducing fatalities and serious injuries at work.

But physical health is a complex phenomenon. Many health professionals today are trained to work within the biopsychosocial framework, which conceptualises health as a product of biological, psychological, and social processes. From this perspective, social factors such as poverty and psychological factors such as poor mental health can exacerbate physical health problems. For example, not having enough money can create anxiety and can limit one’s options for achieving a healthy diet, which in turn negatively impact physical health. It works the other way too – dealing with physical health problems, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, can cause depression or other mental health issues.

In short, just as physical health problems can undermine mental wellbeing, psychological problems, including those caused by financial worries, can negatively impact physical health. Therefore, any approach to employee health and wellbeing must get beyond just the physical, to address the underlying factors that drive poor physical health outcomes in many cases.

Our review of the research literature finds that mental and financial pressures are prevalent among today’s workforce, undermining physical health over the long term and carrying large human and business costs. Poor mental health costs $2.5 trillion globally, and costs UK employers at least £33 billion per annum, in the form of absenteeism, presenteeism, turnover, and lowered productivity. Poor financial wellbeing costs UK employers £1.56 billion annually through absenteeism and presenteeism. It is thus imperative that organisations take a multidimensional approach to employee health and wellbeing. Encouragingly, we find that the majority are doing so, at least with respect to physical and mental aspects of wellbeing.

However, financial wellbeing remains largely off the radar at many organisations. There is less understanding of the role financial worries play in health and wellbeing, as compared to the role of poor mental health, and in how that can impact individual, team, and organisational performance. Many organisations are hesitant to get too involved in employees’ financial wellbeing, due largely to confusion between financial education and financial advice, and the associated organisational responsibility and risk.

More generally, we find that approaches to employee health and wellbeing at the most advanced organisations not only reflect a good understanding of the issues, are innovative, and are experimental, but that they are also consistently strategic, systemic, and take account of the whole person. This is where we see a big opportunity for organisations to refine and improve their wellbeing strategy.

Please see CRF’s earlier report, Employee Health and Wellbeing – Whose Responsibility Is It? for a comprehensive look at the business case for wellbeing. See our full version of this report for more evidence of the business and human costs of poor wellbeing across multiple dimensions, and for definitions of mental and financial wellbeing.

Strategic, Systemic, Whole-person – Crafting a Multidimensional Approach to Employee Wellbeing

Taking a strategic approach to wellbeing is critical for those organisations that want to maximise the positive impact of activities and initiatives upon business outcomes. Developing a more strategic approach requires the organisation to answer several key questions.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE STRATEGIC?

- What is the business strategy? What’s the context? What are the goals and objectives? There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ answer to employee health and wellbeing. What will drive results in each organisation depends on that organisation’s context, its strategy and the related goals and objectives, and the current health profile of the workforce.

- What’s the current health profile of the workforce? Organisations must take the time to identify and understand the specific health and wellbeing challenges their workforces face, in order to appropriately tailor the strategy. Are your people worried about money? Are they getting good sleep and enough exercise? Are they at risk of burnout, or struggling with mental health? How do wellbeing strengths and weaknesses play out among different employee groups? What’s important, to whom in the organisation, and why? Establishing this baseline of the current state of health among the workforce will enable the organisation to then work out priority actions for various segments of the employee population, set objectives and targets, and form a basis for evaluation.

- What activities and interventions are needed? Once the context, business goals, and understanding of the workforce have been established, the organisation can turn toward the question of deciding what to do. Employers can choose between a huge variety of interventions, providers, and delivery options. Organisations will want to ask themselves whether planned activities and interventions match their values and norms? Do they reach beyond just individuals? Have employees’ needs and desires been considered? Have good-quality programmes and providers been selected? How do you know?

- Are activities and interventions systemically interconnected? As noted above, employee health and wellbeing is context-dependent. There is little in the way of ‘golden rules’, and a given organisation’s priorities should be determined primarily by business needs and the current state of health of the workforce. However, we believe that every employer can benefit from conceptualising their organisation as a system of interconnected parts that work together to promote – or undermine – employee wellbeing. It is critical that an organisation’s wellbeing activities, initiatives, and interventions are interconnected in a systemic way. This means that activities should work together to promote the organisation’s overall ability to take care of many problems before they start. This is best achieved by leveraging senior leaders, line managers, the culture, the physical environment, and the nature of the work itself to create a health organisation in which most individuals, managers, and teams can thrive most of the time.

- Are there processes in place to evaluate and evolve the wellbeing strategy? Evaluation is a weak point for many organisations. Nevertheless, it is an important tool for measuring the effectiveness of a given activity or intervention. Has the activity had the desired outcomes, both in terms of impact on employee health/wellbeing and organisational outcomes? Is it providing good value for money? Evaluation is also important for determining how the strategy should evolve. What does the organisation need to do more of? Less of? How are needs shifting among different segments of the workforce?

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE SYSTEMIC?

Organisations often take an overly medicalised approach to employee wellbeing, particularly regarding mental wellbeing (for a detailed discussion of medicalisation and its limitations in addressing employee wellbeing, please see our full report). While mental health first aid and referrals for counselling are helpful and appropriate in some cases, in many other cases the sources of stress and anxiety originate in the organisation itself.

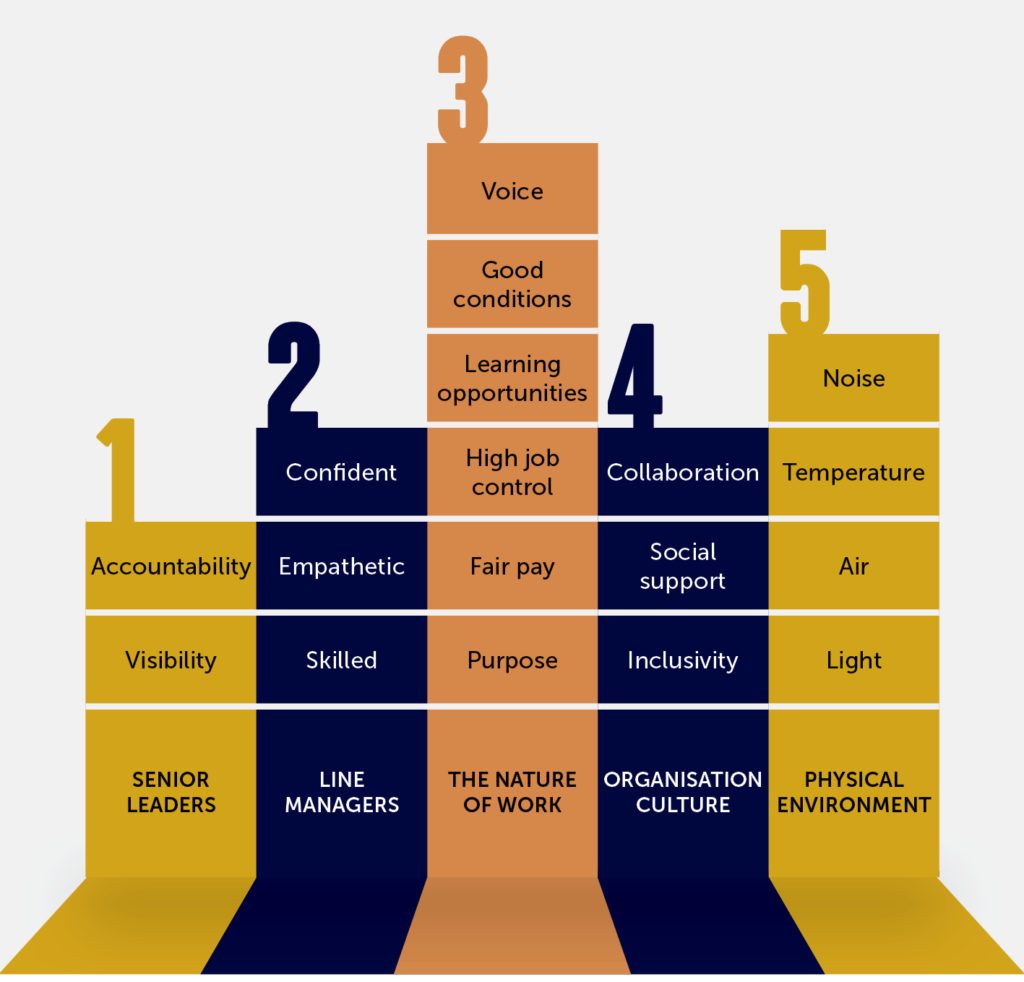

By taking a systemic approach – that is, by aligning health and wellbeing strategy to all the key parts that make up a healthy organisational whole – we believe employers can prevent many problems before they start. Beyond just preventing problems, healthy organisations can also foster positive employee wellbeing, which brings a host of organisational benefits. So what are these key parts, and what does good look like? CRF’s Five Pillars of Organisation Self-Care are senior leaders, line managers, the nature of work, organisational culture, and the physical environment.

CRF’s Five Pillars of Organisation Self-Care

SENIOR LEADERS

Senior leaders set the tone in an organisation. They have an important role to play in starting and sustaining conversations about employee wellbeing, in de-pressurising the work environment and in destigmatising discussions about wellbeing, particularly financial and mental wellbeing.

In short, senior leaders’ role is about visibility and accountability.

When crafting a systemic wellbeing strategy, the key question with respect to senior leadership should be: Does this activity or initiative raise the visibility and/or accountability of senior leadership’s commitment to the agenda?

LINE MANAGERS

Line managers play a critical role in facilitating, or acting as a barrier to, their direct reports’ wellbeing. As authority figures, line managers can have a disproportionate impact on the mood of those they supervise, so it is important that they are skilled, empathetic, and confident managers, able to effectively support others at a very basic level.

Unfortunately, managers are frequently advanced based on technical competence – their ability to manage equipment or process flows – rather than on the basis of their emotional intelligence or good management skills. To make matters worse, they rarely receive practical training to develop these skills.

So what does it mean to be a skilled, empathetic, and confident line manager?

- Skilled – Good people management is a key tool for taking a more preventive, de-medicalised approach to employee wellbeing. So what is good management, with respect to the ‘hard’ skills? Good managers are rich communicators, they are clear about their expectations, they are consistent in their attitudes, behaviours, and values, all across the hierarchy of the organisation, they establish and observe boundaries, they are flexible, able to craft manageable workloads (and recognise unreasonable ones), and they operate on a praise/reward system rather than one of fault-finding (in other words, they focus on strengths over weaknesses).

- Empathetic – In addition to having the ‘hard’ skills of good management, line managers need soft skills. They need empathy, the ability to listen without judging, discretion, intuition, trust, and the ability to be vulnerable. They need to be honest, which means telling the truth even when it’s difficult (for example, by giving accurate feedback on performance, even if it’s negative or the employee is ill). They should be able to respect employees’ ability to make decisions for themselves and to accept the consequences of those decisions. They should show kindness and care, however small.

- Confident – Managers often lack confidence when they have a troubled employee to deal with. They may fear difficult conversations, and face conflicting demands within the organisation about how to handle the problem. For example, the organisation’s Legal and Health & Safety departments may want the manager to avoid risk at all cost, which can encourage the medicalisation of a troubled employee. HR may put too much onus on managers to keep their teams fit and happy, while neglecting other organisational aspects of wellbeing. Finance may want to save money, and so invest in line manager training only sporadically, or skip it altogether.

It is thus unsurprising that line managers, who may also fear the employee’s reaction and want to be a nice person, often opt for a medicalised solution, simply referring a troubled employee to an occupational health physician, an EAP, or an on-site counsellor. While this is sometimes appropriate, many other times line managers can take a more proactive and preventive role, intervening early to help employees cope before problems escalate. But this requires having confidence based on some basic knowledge of how to spot the warning signs of poor wellbeing, good knowledge of what resources are available and how to access them, and what the organisation’s expectations actually are with respect to managing struggling employees.

When crafting a systemic wellbeing strategy, the key question with respect to line managers should be: Does this activity or initiative improve line managers’ capability to respond, both proactively and reactively, to their peoples’ wellbeing needs?

THE NATURE OF WORK

Much has been written about good work – its essential features in modern economies, and how to achieve it. By ‘nature of work’, we mean the conditions and features of a job that make it more meaningful, manageable, and rewarding.

The nature of work that is supportive of employee wellbeing is likely to have the following features:

- Purpose – Work that has a larger purpose (beyond just profit) can foster a sense of meaning for employees. For many people, the sense that they are positively contributing to something larger, such as advancing knowledge, improving society, or simply growing and evolving their business, is one of the major rewards of work. Purpose is intimately connected to relationships and development, and can profoundly shape what an organisation does and how it does it.

- Fair pay – Fair pay has objective and subjective components. Objectively, wages should be high enough for people to live on (as determined by, for example, a Living Wage), and should match or exceed the average for the given qualifications. Subjectively, equal wages should be offered for equal work, regardless of sex, race/ethnicity, or other demographic factors.

- High job control – Job control is defined as the amount of discretion employees have over what they do, when and how. Stanford University’s Jeffrey Pfeffer cites decades of research showing a robust link between high job control and good physical and mental health, across regions. It has a positive impact of individual performance “and is one of the most important predictors of job satisfaction and work motivation, frequently ranking as more important even than pay.” Conversely, low job control is demotivating, hampers learning, and decreases performance. Designing jobs with greater fluidity and autonomy, and erecting barriers to micromanagement, are two useful ways to ensure a good level of job control.

- Learning opportunities – The opportunity to learn and grow, formally and informally, acquiring both general and specific new skills, is a feature of good work. The Health Foundation cites research showing that in-work training can make people happier at work and increase levels of personal wellbeing. Learning isn’t just about going on a course; it’s also about how that knowledge is shared within the organisation.

- Good conditions of work – Good working conditions make a job more manageable. Clear goals, regular opportunities to receive feedback, skill and task variety, flexibility, some measure of job security, and safety are such conditions.

- Voice – According to the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices, employee’s feelings about their work are improved when they have a greater voice in the organisational decisions that affect their jobs. This is true whether employee voice takes the form of direct participation, consultative participation, or some other form.

It is important to note that the value workers place on each of the above is likely to vary, both between people and over the course of a given individual’s life. Nevertheless, jobs that are purposeful, fairly remunerated, have high autonomy and control, opportunities to learn and grow, flexibility, rewarding conditions, and the opportunity to have one’s voice heard are likely to be more attractive, for more people, more often, than those that are purposeless, unfairly paid, lack autonomy and control, have rigid and inconsistent conditions, few or no learning opportunities, and which ignore the employee’s voice.

When crafting a systemic wellbeing strategy, the key question with respect to the nature of work should be: Does this activity or initiative make work more meaningful, manageable, and rewarding?

ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE

Organisational culture and employee wellbeing are intimately linked. Put simply, most employees struggle to thrive in demanding, hostile, and/or conflict-riddled cultures.

What are the features of organisational cultures that support employee wellbeing? We identify the following factors:

- Inclusivity – Healthy organisational cultures are inclusive. Inclusive cultures are about more than diversity. An inclusive culture is an environment that values the different contributions that a diverse workforce can bring. It allows people with different backgrounds, characteristics, and ways of thinking to work effectively together and to perform to their highest potential. Inclusive cultures are psychologically safe, allowing people to speak up and challenge others as appropriate, and without fear of retribution. Organisations with inclusive cultures are able to foster emotional, not just transactional, connections to the workplace among their workforce, and they are effective at creating the conditions for open, destigmatised dialogues around sensitive issues, such as mental or financial wellbeing.

- Social support – Decades of research demonstrate the link between social support and physical and mental wellbeing. For example, research has shown that people with low levels of social support have higher mortality rates, and that friends and family can buffer the effects of the stress, including workplace stress, that can compromise health. Organisations should look for ways to foster social support among employees, both formally and informally, such as by encouraging employees to care for one another and supporting shared connections.

- Collaboration – Organisational cultures that allow employees to thrive are more collaborative than competitive. While some competition can be healthy, employers may want to rethink practices such as forced curve ranking of employees, or the type of language used in job titles or to describe colleagues.

When crafting a systemic wellbeing strategy, the key question with respect to organisational culture should be: Does this activity or initiative help build the kind of inclusive, collaborative, socially supportive culture that attracts, retains, and allows employees to thrive?

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

A physical working environment that is comfortable and accommodating is essential to employee wellbeing. Designing such workplaces isn’t cheap – nor is it always feasible, for non-office-based jobs – but the costs should be weighed against those of absenteeism and turnover. Research from U.S.-based sustainable building and engineering firm Stok, in collaboration with academic partners, finds that a high-quality workplace can reduce absenteeism by up to four days each year. How do they define a high-quality workplace? As one with natural light, good ventilation, and comfortable temperatures.

That a comfortable and accommodating work environment is first and foremost about the basics is supported by other research:

- A study from Cornell University finds that “optimisation of natural light in an office significantly improves health and wellness among workers”, with “workers in daylight office environments reporting a 51% drop in the incidence of eyestrain, a 63% drop in the incidence of headaches, and a 56% reduction in drowsiness.”

- A study from Harvard University shows that improving air quality in an office increases employees’ mental cognition.

- The Future Workplace Wellness study finds that better air quality, access to natural light, and the ability to personalise workspaces are the most important aspects of the physical office environment to employees. Further, “air quality and light were the biggest influencers on employee performance, happiness, and wellbeing, while fitness facilities and technology-based health tools were the most trivial.”

So while fresh fruit and ping-pong tables may be nice perks, they are likely to have limited impact in an office environment that lacks access to natural light, has poor ventilation, is noisy, and is too cold (or too hot). Comfortable and accommodating also means encouraging choice and movement, and understanding that one size does not fit all. For example, many offices have moved to an open plan design, and have built ‘collaboration spaces’ for employees. While these spaces seem to work for extroverts, introverts may need different design solutions. There may also be generational differences in the kind of working spaces that employees prefer. For example, younger workers may be happier to ‘hot desk’ than older workers.

Please see our full report for the specific activities and initiatives that companies are using to strengthen senior leadership engagement, line manager capability, conditions of work, and psychological and physical environments to enhance employee health and wellbeing.

When crafting a systemic wellbeing strategy, the key question with respect to the physical environment should be: Does this activity or initiative help create a physical environment conducive to good physical and mental health?

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO TAKE A ‘WHOLE-PERSON’ APPROACH TO WELLBEING?

In many cases, the sources of poor employee wellbeing – particularly poor mental wellbeing – originate in the organisation itself. We are concerned that many organisations are taking an overly medicalised approach to wellbeing, reflexively labelling employees as ill and reaching for a medical solution – at great cost to the organisation – when a systemic approach to wellbeing strategy could be very effective in mitigating many minor problems before they escalate.

However, while we believe that an overly individualised and medicalised approach to wellbeing has its limitations, we also recognise that even the healthiest organisation will still have sick employees. A ‘whole-person’ approach recognises that employee wellbeing is influenced by several factors, many of which originate outside the workplace. While employers can exercise considerable influence over the way their people are led, managed, the conditions of their work and reward, and the physical and psychological environments in which they labour, they can do far less about employees’ problems that stretch beyond the scope of the workplace, such as dealing with the death of a family member, navigating relationship troubles, or managing the effects of a disease.

What, if anything, can organisations do to boost the wellbeing of employees as whole people, with problems that sometimes have nothing to do with the workplace, yet impact performance in the workplace nonetheless?

One answer is to be found in the concept of resilience.

Resilience is defined as the ability to ‘bounce back’ from setbacks, recover from stressful situations, adapt to challenging circumstances, sustain high performance over time, or simply not become ill when faced with challenging situations.

Tools and strategies that build an individual’s physical and mental resilience may have several advantages:

- They may improve an individual’s ability to cope with personal problems that originate outside work, thus minimising the impact of those troubles on workplace performance

- Equally, by improving an individual’s overall ability to cope, they may help employees deal with stresses that originate inside the workplace, such as rapid change or expanding job responsibilities

- Improved individual resilience may have knock-on effects for the broader organisational culture, as resilient employees who cope well may be good community members and role models for colleagues; in this way, building individual resilience can be seen as one strategy for realising the systemic goal of creating an inclusive, collaborative, and socially supportive organisational culture.

CRF’s 2014 report, Employee Health and Wellbeing – Whose Responsibility Is It?, discusses resilience in-depth.

Here, we highlight a few critical points about resilience:

- Resilience is about both reacting effectively in the moment, and proactively setting oneself up for long-term success.

- Resilience varies from person to person – a positively challenging situation for one person may be highly stressful for another.

- Personal resilience levels can vary over time – the same person may react differently to the same situation at different times.

- While there is some evidence that resilience can be developed, it does not happen overnight, and even the most resilient individual will struggle to thrive in an unhealthy organisation.

Practices That Support a Multidimensional Wellbeing Strategy

We conclude this Speed Read by looking at practices that support the implementation of a multidimensional wellbeing strategy. These practices include taking a data-driven approach, collaborating across boundaries, communication practices, and customisation of the strategy.

A DATA-DRIVEN APPROACH

Taking a data-driven approach to wellbeing strategy means using your workforce data to diagnose problems and drive decision-making, and evaluating the effectiveness of wellbeing initiatives and activities.

Using workforce data to diagnose problems includes practices such as:

- Using complaints/feedback from employees’ and managers’ surveys to verify common problems and solicit views on possible solutions

- Using engagement and pulse surveys to ask people if they feel they are sufficiently supported in terms of wellbeing, and how the organisation can do better

- Reviewing data from EAP, occupational health, and private medical insurance providers to identify the types of issues arising, then targeting wellbeing resources and programming according to need

- Using feedback from employee forums/representative groups to inform decisions about what is needed and how to do it

- Analysis of retention and absence data to identify hotspots, high-risk areas (i.e. night working) and areas of focus

- Tracking reasons for sickness absence and return to work data (i.e. successful returns to work vs. those that leave the organisation).

Evaluation of wellbeing initiatives and activities typically involves looking for changes in employee engagement, absenteeism, and turnover, and assessing the extent to which employees are taking up initiatives.

Our research finds that few organisations are consistently diagnosing or evaluating. There are several reasons that taking a data-driven approach is proving elusive:

- In many organisations, there is simply limited data available.

- Where data exists, it is often incomplete or of poor quality. It may be badly recorded, isolated across a multitude of platforms, or scattered in different formats across multiple providers.

- Confidentiality issues may prevent the organisation from accessing some types of data.

- The organisation may not have the data analytics expertise needed to evaluate the data.

- Wellbeing data is often more subjective than objective; this is particularly true of non-physical data, such as data about employees’ mental health.

But using data can help the organisation understand what its employees value and how its services are being used, and thus can help direct spending more effectively. In short, taking a data-driven approach can lead to actionable insights that are relevant and timely to employees’ needs, thus increasing the chances of deploying successful interventions that will improve individual, team, and organisational performance.

COLLABORATION

As in many areas of HR practice, collaboration across functions can be extremely helpful in driving the wellbeing agenda forward. We encountered many examples of HR collaborating with colleagues, particularly Health and Safety colleagues, to assess needs, craft and disseminate a wellbeing strategy. The connection with Health and Safety makes sense given that, in many organisations, wellbeing has grown out of an earlier focus on employee health and safety in manufacturing and other safety-critical environments.

But as more and more jobs are concentrated in services, and increasingly office-based, we anticipate that the connection between wellbeing and inclusion will increase in importance. Whether responsibilities for inclusion and wellbeing are shared under the broader remit of HR, or whether colleagues will need to reach across functions, we believe that a joined-up approach between organisations’ wellbeing and inclusion strategies is a fruitful way forward. Given the connection between wellbeing – particularly mental wellbeing – and a socially supportive, inclusive culture, we expect colleagues will be able to share evidence, learn from each other and bolster each other’s good practices. At organisations with advanced wellbeing strategies, we are already frequently seeing an alignment of wellbeing to inclusion. The benefits of this include more consistent understanding, and better sharing and cascading of good practices.

COMMUNICATION

A multidimensional health and wellbeing strategy will only be effective to the extent that employees know about it and understand how it benefits them. Communications are an essential tool to achieve this aim.

Good communications also influence data quality and thus the conclusions that you can draw from it – for example, does poor take-up of a wellbeing activity or resource reflect lack of need/interest in it, or was it simply poorly communicated, perhaps targeting the wrong segment of the employee population? Understanding the cause of low take-up has important implications for understanding return on investment.

One of the most important features of an effective wellbeing communications strategy is the targeting of communications by segment of the employee population. For example, black men are twice as likely as white men to die from prostate cancer, while the symptoms of heart attacks are different in women than men, and thus women may not easily recognise them. Targeting wellbeing communications – which includes what is said, to whom it is said, how it is delivered, and what it looks like – may more effectively achieve the multiple aims of educating the audience, supporting inclusion, and gaining a return on investment for a given resource or activity.

For many organisations – especially large ones – a communications strategy that uses a mix of general messages to the whole population and specific messages to sub-groups (such as women, younger employees, and so on) will be most effective; this is also true of the tools used to disseminate communications.

Employers should consider these other features of an effective wellbeing communications strategy:

- Communications should be not only relevant, but timely. ‘Why does this matter to me, and why does it matter now?’

- ‘Pull’ communications, which require the employee to take action (such as navigating to a website to receive the message) are less effective than ‘push’ messages, such as those delivered via app, text message, email, posters, roadshows, briefing sessions, campaigns, and so on. A good strategy both pushes proactively and pulls.

- Branding wellbeing activities and initiatives with a distinctive look and feel can facilitate employee recognition and interaction with them.

- Storytelling, the use of wellbeing champions to share information, and dedicated wellbeing websites or portals on the company intranet are some of the more innovative ways to communicate.

CUSTOMISATION

What do we mean by ‘customisation’? A customisation of wellbeing strategy is a modification of it. That modification may be in the form of a personalisation to the individual – such as the use of wellbeing apps that give individuals information about their sleep and dietary habits, or that deliver mental health support targeted to their specific needs.

But customisation can be thought of in broader terms, such as customising wellbeing strategy to an employee group based on skillset, age, or another factor. One of the most important customisations a large organisation can make to its wellbeing strategy is geographic – customising by site, country, or region.

We found a mix of approaches in our research. Some companies leave each site, country, or region to do their own thing entirely; others roll out one global programme for all colleagues. Leaving each to their own has obvious drawbacks in terms of cost, efficiency, and effectiveness, but equally, there are risks in implementing a generic, universal wellbeing strategy. One global strategy rolled out from a central location is likely to miss the nuances in each context, both in terms of the actual health and wellbeing needs of the employee population, and of the systemic issues that need attention in a given site.

For example, financial wellbeing initiatives will look very different in a ‘saving’ culture as opposed to a ‘spending’ culture, local laws and regulations can pose barriers to certain kinds of initiatives, and the health profile and associated risks of employees in rural versus urban settings is likely to vary considerably, or in advanced industrialised countries as opposed to developing ones. In terms of systemic issues, the opportunities to improve working conditions, such as by increasing flexibility and autonomy, may look very different in a factory as opposed to an office setting, potential adaptions to people’s physical working environment vary by location, and the tone of organisational culture can vary dramatically from one office to another.

We find the most advanced organisations taking a hybrid approach – developing a framework at the global level, that is then customised to be meaningful and effective at local level.

Recommendations

- Remember that business strategy should determine wellbeing strategy.

- Ensure that your strategy takes into account employees’ financial wellbeing.

- Put processes in place to evaluate and evolve the wellbeing strategy.

- Design a wellbeing strategy in which activities and interventions are systemically interconnected.

- Help senior leaders become visible and hold them accountable to your organisation’s wellbeing agenda.

- Ensure that line managers are enablers, not barriers, to their people’s wellbeing.

- Give careful attention to the actual nature and quality of people’s work.

- Don’t neglect organisation culture.

- Audit and adjust the physical environment in which your people work.

- Consider investing in programmes and activities that build resilience among your workforce.

- Determine whether there is value for your organisation in joining up wellbeing and inclusivity.

MEMBER LOGIN TO ACCESS ALL CRF CONTENT